Updates

- Aug 16, 2022. Starting with Pulse 2.0, the ZIP archives were replaced with an SQLite-based document format in order to increase performance and remove the dependencies.

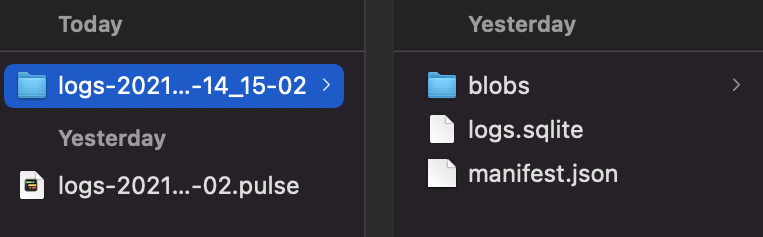

Registering your custom document type and extension is straightforward: you can follow the official sample. The problem is, you can’t just slap any extension1 on a directory to turn it into a file, and Pulse store is a directory containing:

- Manifest (

.json) - Database (

.sqlite) - Directory with blobs

Now, how do you turn a directory into a file? Science!

One of the potential answers is ZIP archives. ZIP archives? What’s so interesting about ZIP archives? They appear entirely ordinary but have some characteristics that make them a common choice for some document formats. There are, of course, other options, and the choice largely depends on your requirements. In this post, I want to share the thought process behind going with ZIP for my specific use case and share some of the implementation details.

Use Case #

What’s the use case? Pulse is a logging system. While running, it stores all of its files in a plain directory (optimized for writing). I primarily care about small write performance in this case. But when you are done logging and want to share or archive the logs, I wanted it to create a document that will appear as a single file with a custom extension to be easily shared and opened on another machine. In this scenario, I care about space efficiency, but not about incremental updates or atomic writes.

Apple Document Types #

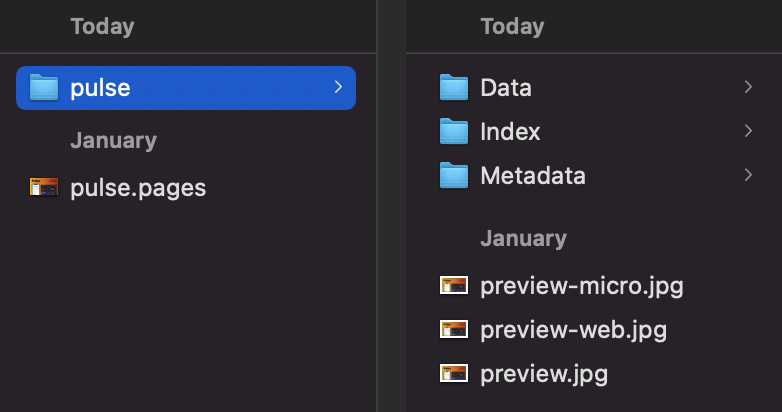

Archives (.pages) #

Pages files are ZIP archives2. You can change the extension to .zip and unarchive it (or use unzip from Terminal).

When you open a document, Pages unarchives it and puts it in memory. Archiving a Pages document makes a lot of sense as it saves a bit of space.

You can think of a ZIP archive as a key/value storage, optimized for the case of write-once/read-many and a relatively small number of distinct keys. ZIP is easy to use, it’s ubiquitous and fast.

One of the main disadvantages of ZIP, or other binary formats, is its content is inaccessible making it impossible to use with source control.

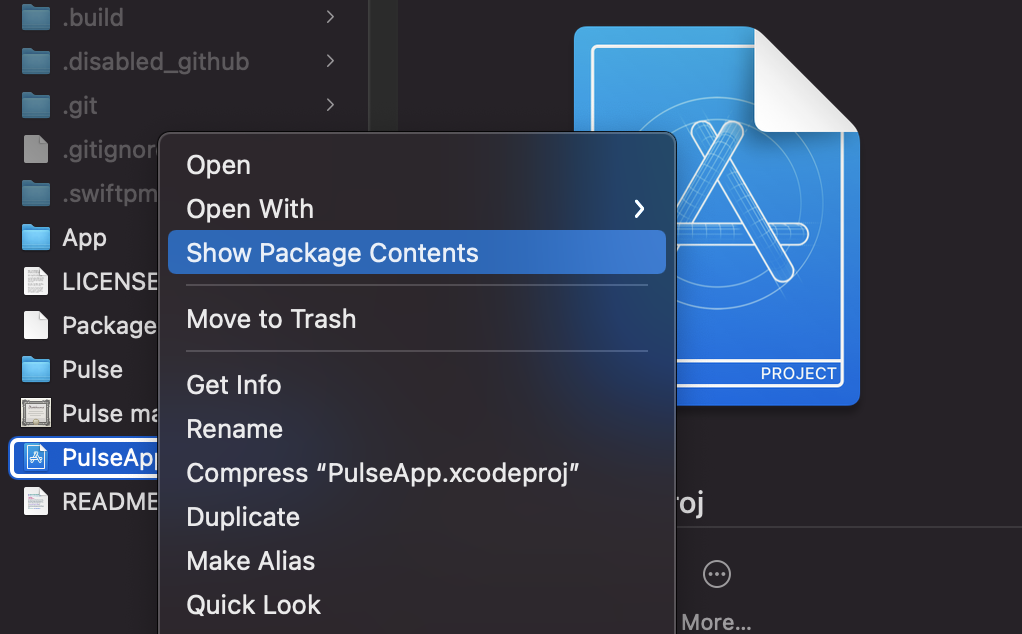

Packages (.pbxproj) and Bundles (.app) #

Xcode project files also consist of multiple files, but they are not archives.

Xcode project files are packages (a macOS concept). It is a directory displayed to the user as a single file.

Unlike archives, which are just binary blobs, packages can be added to source control, which is the main reason .pbxproj files are packages.

There are many other document types that Apple represents as Packages or Bundles3: apps (.app), photo libraries (.photoslibrary). A great advantage of packages is that they don’t require any special code, FileManager can simply directly access the files and the directory inside the package. While packages can be operated directly by FileManager, there’s also a rich API called FileWrapper which can help working with packages and ensure data integrity.

Other Approaches #

Apple typically uses packages and archives, but there are also a couple of other approaches to consider.

SQLite #

It might sound counterintuitive at first, but SQLite claims to be an excellent document file format. From the listed advantages, I would like to point out two things:

- Atomic Transactions. Writes to SQLite are atomic meaning there is practically no danger of corrupting the document. This is pretty much impossible to achieve with “pile-of-files” approaches.

- Performance. For relatively small files, SQLite claims to be 35% faster than the filesystem. SQLite excels at small atomic writes because it uses a tail-add journal which is sympathetic to the way nvram works. But this is irrelevant for my scenario where I don’t care about incremental updates at all.

Binary Formats #

.sqlite and .zip are both binary formats. Nothing stops you from defining your own, just like some people come up with custom networking protocols. And just like with networking, it’s almost always best to stick with one of the existing formats.

Pulse Store (.pulse) #

As I mentioned in the beginning, I decided to go with ZIP archives. The primary reasons: space savings4 and ease of use. Logs typically have a lot of repetitive data, the savings can be massive. Pulse documents are also only used for sharing, so the potential inefficiencies of ZIP incremental updates weren’t a concern.

ZIPFoundation #

To implement archiving, I use ZIPFoundation. Unlike other libraries, it doesn’t have any binary dependencies and uses Apple’s Compression framework.

Creating an archive:

func copyStore(to storeURL: URL) throws {

let tempDirectoryURL = // ... create temporary directory

// ... create copy of the store ...

// ... create copy of the blobs ...

// ... generate manifest ....

// Create archive

try FileManager.default.zipItem(

at: tempDirectoryURL,

to: storeURL,

shouldKeepParent: false,

compressionMethod: .deflate, // You have an option not to

progress: nil

)

try FileManager.default.removeItem(at: tempDirectoryURL)

}

When I create a copy of a database, I set “journal_mode” to “OFF” to ensure there is no .wal file.

Opening an archive:

final class LoggerStore {

private var archive: Archive?

init(storeURL: URL) throws {

guard let archive = Archive(url: storeURL, accessMode: .read) else {

throw // ...

}

let manifestData = try archive.dataForEntry["manifest.json"]

let manifest = try JSONDecoder().decode(Manifest.self, manifestData)

let unarchivedURL = FileManager.default.temporaryDirectory

.appendingPathComponent("com.github.kean.pulse", isDirectory: true)

.appendingPathComponent(manifest.id)

if !FileManager.default.fileExists(atPath: unarchivedURL.path),

let database = archive["logs.sqlite"] {

try archive.extract(database, to: unarchivedURL + "logs.sqlite")

}

// ...

}

}

private extension Archive {

func dataForEntry(_ name: String) throws -> Data {

guard let entry = index[name] else { // `index` made by the app

throw // ...

}

var data = Data()

_ = try self.extract(entry) { data.append($0) }

return data

}

}

The great thing about ZIP archives is they are random access. Some archives, e.g. .tar.gz, have inter-file compression, but ZIP doesn’t. It allows you to access individual files without unarchiving the whole thing. This is perfect!

Archivedoesn’t implement aRandomAccessCollectionprotocol (onlySequence) but provides asubscript(path: String)which can be a bit misleading. If you look at the implementation, every time it gets called,Archiveiterates over the central directory on disk in a sequential fashion (O(N)). I ended up constructing my own in-memory index of entries when the store is opened.

As mentioned earlier, each Pulse store has a manifest (.json), a database (.sqlite), and a directory for blobs. While a database is usually relatively small, blobs can grow quite a bit because that’s where all the network responses are. I have to unarchive a manifest and a database when opening a store, but with zip I can keep the blobs in an archive and access each individual blob on-demand (see dataForEntry).

Blob store has another optimization in place where responses automatically get deduplicated. It calculates a cryptographic hash (sha1) for each response. If two responses have the same hash, only one blob gets stored. This is great especially if the app keeps fetching the resource that doesn’t change over and over again.

Opening Documents #

Setting the supported document type was pretty easy. I just followed the sample code. After adding the document type to the plist, I got the system to recognize my documents and even auto-generate an icon.

When the user double-clicks the document, the app receives an onOpenURL() callback.

struct AppView: View {

var body: some View {

ConsoleView()

.onOpenURL(perform: model.openDatabase)

}

}

Another approach is to use DocumentGroup, but it comes with its own caveats. For a simple scenario like this onOpenURL() can do.

Adding a custom document type is just part of the job. I’m now also working on QLPreviewingController to offer previews with some store metadata, and more.

Conclusion #

A clear, concise, and easy to understand file format is a crucial part of any application design. Make sure to chose the format that works best for your requirements.

Data dominates. If you've chosen the right data structures and organized things well, the algorithms will almost always be self-evident. Data structures, not algorithms, are central to programming.

References

-

Unless it’s a special extension of a document type registered to be a package, will talk about it later in the post. ↩

-

Turns out, if your document is 500 MB or larger, you might be asked to save your document, spreadsheet, or presentation as a package. ↩

-

There is a distinction between Packages and Bundles that I’m not going to cover, you can read more online. ↩

-

ZIP archives can also work without compression if you just want to put multiple files in a single binary. ↩