The key for solving any problem is decomposition. The grammar defined in the previous article is composed of multiple tiny pieces chained together. The question is, how do we translate it into code?

One of the options is to use parser generators. This is a great option and I will probably revisit it in the future posts. But this one, it’s about something else.

Parsing Ranges #

Let’s start with a relatively simple non-terminal symbol - Range Quantifier. There are three versions of range quantifiers:

- a

{n}– matches “a” exactly n times - a

{n,}– matches “a” at least n times - a

{n,m}– matches “a” from n to m times

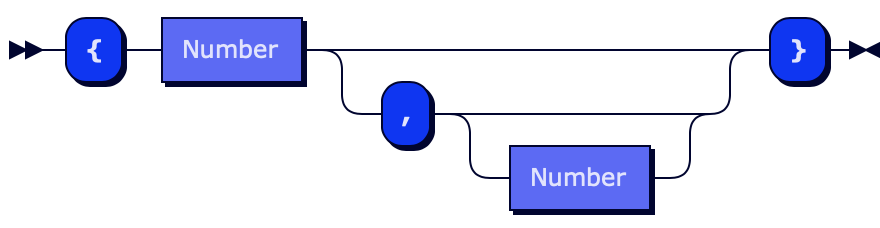

This is the grammar for the range quantifier defined in the previous article:

RangeQuantifier ::= "{" Number ( "," Number? )? "}"

Start with a Function #

How do we approach this? It’s usually best start with a function.

func parseRangeQuantifier(_ string: Substring) -> (RangeQuantifier, Substring)? {

fatalError("Not implemented")

}

The parseRangeQuantifier function returns a range quantifier along with the remaining string if it finds a match. It returns nil if no match is found.

First, let’s check whether the first character in the input string is “{“ or not.

func parseRangeQuantifier(_ string: Substring) -> (RangeQuantifier, Substring)? {

var string = string

guard string.first == "{" else {

return nil

}

string.removeFirst()

// ...

}

The opening “{“ indicates that the string that we are looking at might, in fact, represent a range quantifier.

The next part of the range quantifier is a lower bound which must be a non-negative number. Parsing it is a bit trickier.

func parseRangeQuantifier(_ string: Substring) -> (RangeQuantifier, Substring)? {

// ...

var digits = [Character]()

while let digit = string.popFirst(), CharacterSet.decimalDigits.contains(digit) {

digits.append(digit) // Starting 0 is also fine for now

}

guard let lowerBound = Int(String(digits)) else {

return nil

}

// ...

}

This is already becoming unwieldy. And it doesn’t even remotely look like the original grammar.

RangeQuantifier ::= "{" Number ( "," Number? )? "}"

We are clearly not going to get far by continuing with this strategy. The first thing that we could do to improve the implementation is extracting some of the parsers from the original function. We are most likely going to need these separate parsers later anyway.

There are two parsers total to extract. The first one checks whether the input string has the given prefix and returns Void if it does. The second one parses a non-negative number from the input string.

func parseString(_ prefix: String, _ string: Substring) -> (Void, Substring)? {

string.hasPrefix(prefix) ? ((), string.dropFirst(prefix.count)) : nil

}

func parseNumber(_ string: Substring) -> (Int, Substring)? {

var string = string

var digits = [Character]()

while let digit = string.popFirst(), CharacterSet.decimalDigits.contains(digit) {

digits.append(digit)

}

guard let number = Int(String(digits)) else {

return nil

}

return (number, string)

}

This starts to look better. Now let’s try combining these functions.

func parseRangeQuantifier(_ string: Substring) -> (RangeQuantifier, Substring)? {

guard let (_, stringA) = parseString("{", string),

let (lowerBound, stringB) = parseNumber(stringA) else {

return nil

}

return (RangeQuantifier(lowerBound: lowerBound, upperBound: 0), stringB)

}

This definitely works, but it’s far from being perfect. We had to manually pass the input string from one parser to another. It was tedious to write. And there is a room for error. And, more importantly, we buried the original intent – we simply expect a “{“ followed by a number – under all of these technical details. Yikes! There must be a better way.

Abstract Parser #

Let’s go back to the original definition of the range quantifier parser.

func parseRangeQuantifier(_ string: Substring) -> (RangeQuantifier, Substring)?

You don’t have to look closely to notice that it is almost identical to the two other parser definitions that we introduced.

func parseString(_ prefix: String, _ string: Substring) -> (Void, Substring)?

func parseNumber(_ string: Substring) -> (Int, Substring)?

These seem like three instances of the same pattern. It’s time for an abstraction!

struct Parser<A> {

let parse: (_ string: Substring) throws -> (A, Substring)?

}

Another option was to start with a generic function, but struct enables more possibilities. For example, you can add extensions to a struct which will come in handy later in the article.

Let’s define a few parsers, this time starting from bottom-up. The first parser will be equivalent to the parseString function introduced earlier. The original implementation of the function will do just fine, all we need is to wrap it in a Parser.

struct Parsers {}

extension Parsers {

static func string(_ p: String) -> Parser<Void> {

Parser { str in

str.hasPrefix(p) ? ((), str.dropFirst(p.count)) : nil

}

}

}

I introduced

Parsersstruct to nest parser definitions inside it so that they won’t pollute the global namespace. I will omit it in the next code samples.

Parser Combinators #

Let’s now deal with numbers. I think in this case we can do better than the original function. What is a number (natural and zero)? It is just one or more digits in a row (we ignore the starting 0 for now). Let’s try to represent this idea as closely to the definition as possible.

We can start with something as simple as reading a single character from an input string.

let char = Parser<Character> { str in

str.isEmpty ? nil : (str.first!, str.dropFirst())

}

This is great, but we must accept the character only if it represents a digit. You can do that with a filter method which you’ll probably find familiar.

let digit = char.filter(CharacterSet.decimalDigits.contains)

How do you implement filter?

extension Parser {

func filter(_ predicate: @escaping (A) -> Bool) -> Parser<A> {

map { predicate($0) ? $0 : nil }

}

}

The method takes the current parser and the predicate as an input and produces a new parser as an output. Congratulations, this is the first parser combinator that we encounter. There is going to be many more!

A parser combinator it is a higher-order function which accepts one or more parsers as input and produces a new parser as output.

The filter method takes the value from the given parser and if the value passes the predicate, returns this value from the parser which it returned as an output. If the value doesn’t pass the predicate, it returns nil indicating failure.

You might be wondering, where did map come from? This is another parser combinator, let’s also implement it along with its friend flatMap.

extension Parser {

func flatMap<B>(_ transform: @escaping (A) throws -> Parser<B>) -> Parser<B> {

Parser<B> { str in

guard let (a, str) = try self.parse(str) else { return nil }

return try transform(a).parse(str)

}

}

func map<B>(_ transform: @escaping (A) throws -> B?) -> Parser<B> {

flatMap { match in

Parser<B> { str in

(try transform(match)).map { ($0, str) }

}

}

}

}

maptakes a value produced by the given parser and returns a new parser which produces a transformed valueflatMapreturns a parser which produces the result of the parser returned by thetransformclosure. Thetransformclosure is called when the current parser matches a value.

These two functions are a bread and butter of functional programming, or I would dare to say, programming in general. Array has them, Optional has them, Future has them, Combine and RxSwift primitives have them. And now Parser has them too, making it a proper functor and monad.

We’ve already covered a lot of ground but bear with me, there is one more method that we need to finally define the number parser - oneOrMore.

extension Parser {

/// Matches the given parser one or more times.

var oneOrMore: Parser<[A]> {

zeroOrMore.map { $0.isEmpty ? nil : $0 }

}

/// Matches the given parser zero or more times.

var zeroOrMore: Parser<[A]> {

Parser<[A]> { str in

var str = str

var matches = [A]()

while let (match, newStr) = try self.parse(str) {

matches.append(match)

str = newStr

}

return (matches, str)

}

}

}

We now have everything that we need to define a number parser.

let number = digit.oneOrMore.map { Int(String($0)) }

let digit = char.filter(CharacterSet.decimalDigits.contains)

Bringing It Together #

We should now have everything to parse a range quantifier. There is one last missing piece of the puzzle - zip.

/// Matches only if both of the given parsers produced a result.

func zip<A, B>(_ a: Parser<A>, _ b: Parser<B>) -> Parser<(A, B)> {

a.flatMap { matchA in b.map { matchB in (matchA, matchB) } }

}

func zip<A, B, C>(_ a: Parser<A>, _ b: Parser<B>, _ c: Parser<C>) -> Parser<(A, B, C)> {

zip(a, zip(b, c)).map { a, bc in (a, bc.0, bc.1) }

}

// func zip<A, B, C, D>) ...

With the addition of zip we can now clearly represent what tokens we expect and in which order.

let rangeQuantifier = zip(

string("{"), number, string(","), number, string("}")

).map { _, lowerBound, _, upperBound, _ in

RangeQuantifier(lowerBound: lowerBound, upperBound: upperBound)

}

rangeQuantifier.parse("{1,3}") // Returns 1...3

rangeQuantifier.parse("{1,3") // Returns nil

If you remember the grammar for range quantifiers, it allows the upper bound to be optional. It’s time for another parser combinator - optional.

func optional<A>(_ parser: Parser<A>) -> Parser<A?> {

Parser<A?> { str -> (A?, Substring)? in

guard let match = try parser.parse(str) else {

return (nil, str) // Return empty match without consuming any characters

}

return match

}

}

let rangeQuantifier = zip(

string("{"), number, string(","), optional(number), string("}")

).map { _, lowerBound, _, upperBound, _ in

RangeQuantifier(lowerBound: lowerBound, upperBound: upperBound)

}

rangeQuantifier.parse("{1,3}") // Returns 1...3

rangeQuantifier.parse("{1,3") // Returns nil

rangeQuantifier.parse("{1,}") // Returns 1...

Perfect! We’ve just introduced most of the parser quantifiers that you will ever need. We used them to successfully implement a parser for part of the regex grammar. Turns out, almost the entire regex grammar can be represented using just these few concepts!

The new parser looks great, but I think we could make it even better.

Tidying Things Up #

We are going to need to write and combine a lot of tiny parsers to fully cover the entire regex grammar. Every bit of readability counts. Ideally we want our parser to match the grammar as closely as possible.

RangeQuantifier ::= "{" Number ( "," Number? )? "}"

The first easy win is to make parsers expressible by string literals:

extension Parser: ExpressibleByStringLiteral where A == Void {

/// ...

public init(stringLiteral value: String) {

self = Parsers.string(value)

}

}

We can now omit explicit calls of string function:

let rangeQuantifier = zip("{", number, ",", optional(number), "}")

.map { _, lhs, _, rhs, _ in RangeQuantifier(lhs, rhs) }

Much better. Most people should probably stop on this version. The code already looks perfectly fine. But if you want to push it a little bit further, there is always a way!

Notice how we had to explicitly ignore some of the arguments in map? This is something we can address. How? With these three operators:

infix operator *> : CombinatorPrecedence

infix operator <* : CombinatorPrecedence

infix operator <*> : CombinatorPrecedence

func *> <A, B>(_ lhs: Parser<A>, _ rhs: Parser<B>) -> Parser<B> {

zip(lhs, rhs).map { $0.1 }

}

func <* <A, B>(_ lhs: Parser<A>, _ rhs: Parser<B>) -> Parser<A> {

zip(lhs, rhs).map { $0.0 }

}

func <*> <A, B>(_ lhs: Parser<A>, _ rhs: Parser<B>) -> Parser<(A, B)> {

zip(lhs, rhs)

}

precedencegroup CombinatorPrecedence {

associativity: left

higherThan: DefaultPrecedence

}

With these operators we can dramatically reduce the amount of the code needed:

let rangeQuantifier = ("{" *> number <* "," <*> optional(number) <* "{")

.map(RangeQuantifier.init)

Brilliant! This is as close to the original grammar as we can get (we can still push it a little bit further but I don’t think there is a reasonable way to).

You might still prefer the previous version without operators, but I think this is one of the very few cases where the addition of custom operators is appropriate:

- These operators are going to be used very often

- If you were to use functions instead, there is no clear way of naming them

- These are the new operators, we are not overloading the existing ones

Remaining Steps #

We haven’t added support for the following definition:

- a

{n}– matches “a” exactly n times

I will leave this as an exercise to the reader.

We also allow numbers that start with zero, e.g. “012” or “0012”. This is not great, not terrible – other regex parsers also do that.

Theory Break #

Unlike the previous article, I haven’t yet touched any of the theory behind parsing.

Parsing is a well-researched area. It’s impossible to cover everything in a single article so I’m going to leave this note here for additional reading:

Parsing Techniques (Additional Reading)

There is a huge taxonomy of parsing techniques.

In top-down parsing method, the tree is reconstructed from the top downwards. The opposite is bottom-up parsing which starts by recognizing the leaf nodes and constructing the tree from the bottom.

Non-directional methods construct the parse tree while accessing the input in any order they see fit. This, of course, requires the entire input to be in memory before parsing can start. Directional parsers access the input tokens one by one, in order, all the while updating the partial parse tree.

Parsing methods can also be classified by the search technique. In general, there are two methods for solving problems which have more than one alternative path in the solution. They are depth-first-search and breadth-first search. The former is also associated with backtracking. If the grammar is deterministic (it doesn’t have any alternatives), the parsing can be done using linear methods. If the parser does a pre-determined look-ahead to determine which production to use, it can still be classified as deterministic. Different parsing techniques have different time complexity.

A parser can be generated from the grammar or written by hand.

Each technique is best suited for recognizing a specific type of grammar. You can read all about them in a Parsing Techniques book by Dick Grune and Ceriel J.H. Jacobs which is a definitive resource on parsing.

The method used in this article is called LL(1) parser. It is one of the most popular ones. The first “L” stands for “left-to-right, the second “L” for “identifying the leftmost production first”, aka “top-down parsing”. “(1)” stands for “linear” – there is no backtracking or other search technique needed. This method has limitations but it is great for simple context-free grammars.

We wrote the parser by hand (we haven’t generated it) using Parser Combinators technique. But the code is so similar to the formal grammar that the process of writing this parser was very similar to defining a formal grammar for a parser generator.

We also didn’t keep a parse tree around and only kept the semantics. This is something that you might want to keep an eye for when writing your parsers.

Completing the Parser #

We wrote the first tiny piece of the regex parser and we just need to finish the rest now. It’s not going to be easy and there are still more concepts to learn. If you do everything right, you end up with a parser that can take a regex pattern like “the ((red|blue) pill)” and turn it into this (AST):

– Expression

– String("the ")

– Group(index: 1)

– Expression

– Group(index: 2)

– Alternation

– String("red")

– String("blue")

– String(" pill")

Throwing Errors #

If you noticed, the original parser was defined as a throwing function.

struct Parser<A> {

let parse: (_ string: Substring) throws -> (A, Substring)?

}

You can use this property to throw an error when parser enters a state which it can’t recover from.

extension Parser {

func orThrow(_ message: String) -> Parser {

Parser { str -> (A, Substring)? in

guard let match = try self.parse(str) else {

throw ParserError(message, str.index)

}

return match

}

}

}

let rangeQuantifier = "{" *>

number.orThrow("Range quantifier is missing lower bound") <* /* ... */

With this change, if the parser encounters a “{“ it fully commits to producing a range quantifier or dies trying. If it fails, it produces a clear diagnostic message along with the index where the error occurred.

Choice #

If there are multiple potential matches at any given state, you can use oneOf function to select the first parser that matches.

func oneOf<A>(_ parsers: Parser<A>...) -> Parser<A> {

precondition(!parsers.isEmpty)

return Parser<A> { str -> (A, Substring)? in

for parser in parsers {

if let match = try parser.parse(str) {

return match

}

}

return nil

}

}

Recursive Constructs #

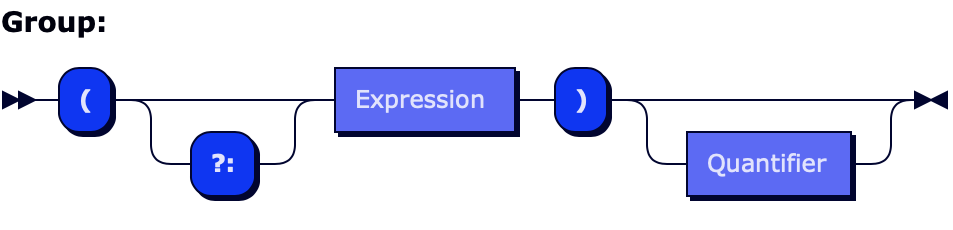

Some constructs are defined recursively. For example, a group can contain other groups among other subexpressions.

Group ::= "(" GroupNonCapturingModifier? Expression ")" Quantifier?

GroupNonCapturingModifier ::= "?:"

Fortunately, parser combinators are capable of handling (left) recursion just fine:

let group = ("(" *> optional("?:") <*> expression <* string(")").orThrow("Unmatched opening parentheses")).map(Group.init)

let expression = oneOf(match, anchor, lazy(group))

This is a simplified version of the grammar, see kean/Regex for the full version.

There are two things to be aware of:

expressionparser must stop when it encounters a closing parentheses “)” and, by doing that, give control back to thegroupparserlazyfunction wrapsgroupdefinition into a closure (it’s marked with@autoclosure). If we don’t do that, it will crash in runtime because thegroupconstant is defined using itself. And because it uses itself indirectly, the compiler can’t produce a diagnostic to warn us.

Time Efficiency #

As I previously mentioned, the method used in this article is called LL(1) where “(1) stands for “linear”. It means that the parser guarantees to produce a result in linear time. It can do that because it is fully deterministic – it always knows which production to use by just looking at the first unprocessed character.

Sometimes a parser might need to look ahead a few symbols to know which production to use. The parsers which involve a constant look-ahead are called LL(k) parsers, where “k” stands for the length of the look-ahead.

The alternative to linear/deterministic parsers are parers which can’t determine which production to use by just looking at one character. These parsers involve a search technique, for example, backtracking, which might be very expensive.

You can read more about LL(1) and other parsing techniques in “Parsing Techniques”] by Dick Grune and Ceriel J.H. Jacobs.

Drawbacks #

No technology is without drawbacks. It’s hard to find many with parser combinators – this a simple but truly powerful concept.

The only major drawback that I found was that, just like with any other declarative system, like SwiftUI, or Auto Layout, or RxSwift, if there is a problem, debugging it might become a nightmare. Fortunately, these parsers are modular making it easy to cover them with unit tests.

On the other hand, I would imagine that debugging parser combinators is still going to be easier than debugging a parser generated by a sophisticated tool which you don’t necessarily have a complete understanding of.

What’s Next #

Parser combinators (or monadic parsers) are a great example of functional programming used to bring practical benefits. The introduced notation makes parsers compact and easy to read to the point that it becomes almost like reading a formal grammar. Parsers can be expressed in a modular way using just a few familiar concepts, like map, filter, zip, and others.

In contrast with parser generators, this method of building parsers is fully extensible. You can use the full power of Swift or any other programming language to define special combinators or special parsers of any kind. There is also very little you need to learn before you can start using parser combinators, especially if you are familiar with functional programming.

The code from the article is available in a playground. You can find the complete regex parser implementation in kean/Regex. With a parser completed, we can now produce a structured representation of the pattern and compile it. This will be the focus on the upcoming article. Stay tuned!

References

- Brandon Williams, Stephen Celis (June 2019), Parser Combinators, Point-Free, A video series exploring functional programming and Swift

- Graham Hutton, Erik Meijer (1996), Monadic Parser Combinators, Department of Computer Science, University of Nottingham

- Dick Grune, Ceriel J.H. Jacobs (2008), Parsing Techniques, VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

- Scott Wlaschin (2016), Understanding Parser Combinators: A Deep Dive (Video), NDC Conferences

- Gunther Rademacher, Railroad Diagram Generator