The parser, introduced in the previous article, produces an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). AST is a structured representation of the pattern which is easy to manipulate. Now, the question is how to turn it into something that can be evaluated to check if it matches an input string.

Fortunately, there are very few concepts that you need to know, most of which we already covered in the previous articles. In this article, you will start seeing all the pieces coming together. Are you excited?

Regular Languages #

In Regex, Part 1: Grammar I briefly mentioned Chomsky Hierarchy of grammars. In Regex, Part 2: Parser we implemented a parser which recognizes a regular expression language. This is a Type-2 language (or context-free language). Chomsky Hierarchy states that you need a Pushdown Automatin to recognize it. This is essentially what we implemented using Parser Combinators, but without mentioning it explicitly (there was already too much theory to go through!).

Now, if you look at Chomsky Hierarchy more closely, there is also Type-3 grammars (or regular grammars) which define regular languages. This sounds familiar, doesn’t it? It says that you need Finite State Automaton to recognize these languages. What does it all mean?

There are a lot of parallels between what we were doing in the previous articles and what we are going to do next:

| Grammar | Languages | Automaton |

| Type 2 | Context-free* | Pushdown Automaton |

| Type 3* | Regular | Finite State Automaton |

* In our case, these both of these are the same thing – regular expression language. We used Pushdown Automaton to recognize a regular expression language (Type-2 language). And now we will use this language to generate Finite State Automaton.

At this point, you are either excited or confused. If it’s the later, don’t worry, continue with the series and revisit it later.

Pushdown Automaton (Additional Reading)

You don’t have to know Pushdown Automaton to continue going through this series, as you didn’t need it to know it to implement Parser Combinators. However, it is one of the fundamental computational models which is important to understand. It essentially introduces a concept of a stack. In the case of Parser Combinators, a stack was implicitly created by recursive function calls.

Finite State Machines #

A finite state machine (or FSM for short) is a mathematical model of computation. It has a finite number of states, one of which is the initial state. It can transition from one state to another based on the input and the conditions of the transition. It can be in exactly one of the states at any given time.

There are many different kinds of state machines. Some state machines perform actions when they enter or exit the state or perform a transition. Some state machines can have nested states. Etc. You can read about this wonderful world of state machines later if you are interested. But in this article we are only going to focus on one type of state machines - acceptors.

Acceptors #

Acceptors (also called recognizers) are one of the simplest types of state machines. The job of an acceptor is to produce a binary output (true of false) indicating whether the received input is accepted. This is exactly what we are looking for.

This is just enough theory to get started. If we need some additional concepts later, we will introduce them as we go.

Representation #

There are multiple ways to represent state machines. The implementation that I used represents each State as a class (to maintain identity), which contains an array of transitions. It has an advantage of being small and making it easy to combine multiple state machines, but a disadvantage of introducing cycles between states.

Compiler #

The compiler in Regex takes AST as an input parameter and produces a compiled regex as an output. The compiled regex contains a state machine produced by the compiler along with some metadata like capture groups.

To compile an AST, the compiler needs to traverse the tree. It does that by compiling each of the subexpressions recursively starting from the root.

I’m not including any of the code from the compiler in this article because there is really nothing special about it. What is truly important is all the concepts behind it. But if you’d like to ground these concepts into code, I would still recommend going through Compiler.swift and the related files. I kept the implementation as small and simple as possible, making it easier to follow and see the underlying concepts.

Match Character #

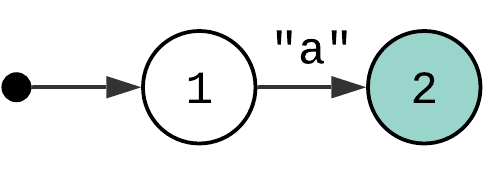

Let’s start with probably the simplest possible regex pattern consisting of a single character: "a". The AST for this pattern is just a single construct – Match.character("a")).

This regular expression can be represented using a state machine with an initial state (1), an accepting state (2) and a transition between them with the condition that the input character must match "a".

How do you “run” this state machine? You take the input string, starting from the first character. Then you check what transitions are possible from the initial state. In this case, there is only one transition – a transition to state 2 if the input matches “a”. You check the condition, and if it returns true, you perform a transition to the next state. State “2” is an accepting state. If the machine enters this state, the match is found.

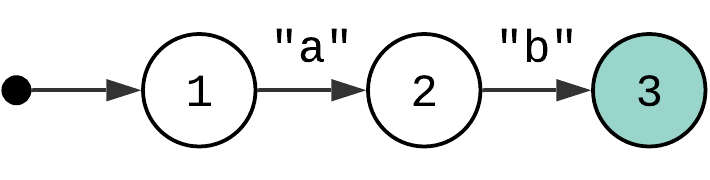

What if instead of one there were two characters in the pattern, e.g. “ab”? You add a new state and a new transition to the state machine.

String-Searching Algorithms (Additional Reading)

In reality, a naive string-search algorithm that checks each character one-by-one will be inefficient. There is a faster way to do that. A pattern consisting of multiple characters in a row can be compiled into a state machine with a single transition with a condition “does an input string has the given prefix?” (

string.hasPrefix(:)). This will allow the matcher to use one of the faster string searching algorithms and improve the time complexity fromO(nm)toO(n+m), wherenis the size of the input andmis the size of the pattern. Regex also performs this optimization.

Match Character Class #

There is only one difference between a state machine which matches a specific character and one which matches a character from a character class. It is a condition of the transition. In the case of character classes, the condition needs to check whether the input character belongs to the given character class.

One of the ways to represent character classes in Swift is with CharacterSet type from the Foundation framework. But there are a few caveats.

Extended Grapheme Clusters (Additional Reading)

When you talk about characters and strings you have to talk about extended grapheme clusters.

CharacterSetworks withUnicode.Scalars. But a single user-perceivedCharacter(or extended grapheme cluster) might contain multiple Unicode scalars. For example, a single 👩💻 emoji consists of three Unicode scalars[👩 128105, 8205, 💻 128187]where8205is a special Zero-Width Joiner character.Now, the question is, if the user types a regex pattern “[👩💻]” which strings will it match? Regex simply adds all the Unicode scalars into a character set. When it performs a match, it checks whether the character set contains all of the Unicode scalars from the input character. This behavior might differ in other regex engines and it is something to keep in mind.

Quantifiers #

Quantifiers specify how many instances of a character, group or character class must be present in the input for a match to be found. We need to introduce a new type of transition to implement quantifiers – an epsilon transition (or ε). This is a transition which changes the state but doesn’t consume any of the input characters.

One or More Quantifier #

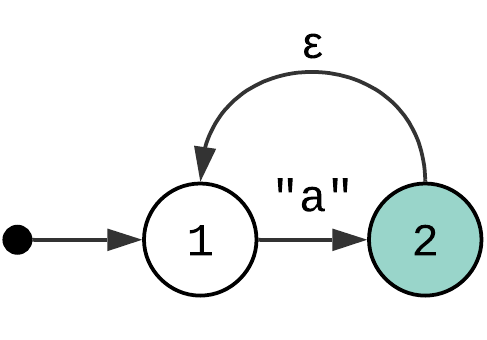

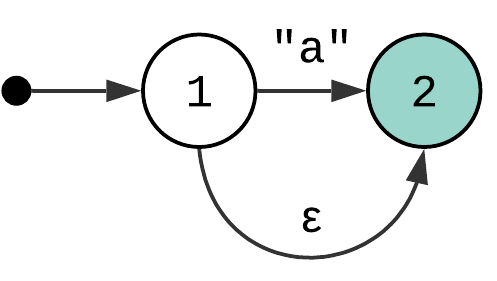

One or more quantifier (or “+”) matches the input one or more times. Here is a state machine that represents a “a+” pattern:

We took a simple Match Character state machine and added a single epsilon transition to turn it into “match character a one or more times” state machine. Now, how does this work? A new transition creates a loop (or cycle) in the state machine. When you reach state 2, you now have an option to go back to state 1 and consume character “a” one more time. And then repeat.

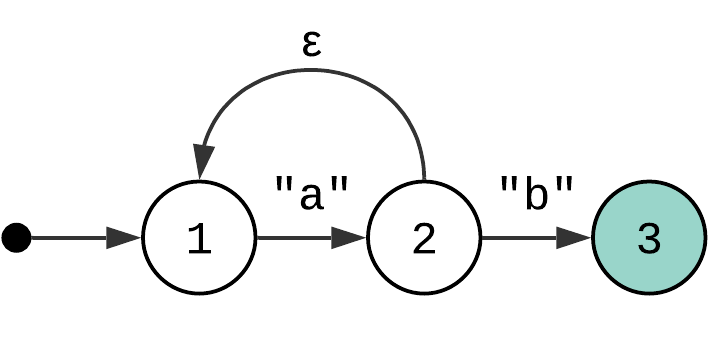

In the current state diagram, “2” is the accepting state. But nothing prevents us from extending it. Let’s say we add a letter “b” to the pattern: “a+b”.

This state machine accepts strings like “a”, or “aab”, or “aaab”. It works because when you reach state 2 and the next character in the input is not “b” yet, you still have an option to go back and try consuming more characters “a”.

Zero or One Quantifier #

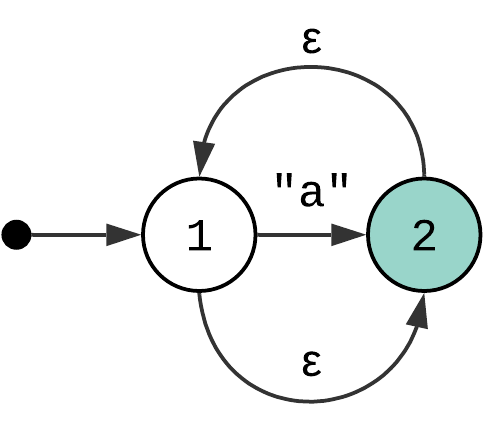

Zero or one quantifier (or “?”) matches the input zero or one times. I personally call it “optional” quantifier. The state machine that represents it is very similar to the previous ones:

The difference here is that the epsilon transition allows you to skip matching the character “a” entirely. And keep in mind, I use simple Match Character patterns here only as an example. You can put any state machine between states 1 and 2 to have “zero or one” quantifier applied to them.

Zero or More Quantifier #

Zero or more quantifier (or “*”) matches the input zero or more times. The state machine that implements it looks like a combination of the previous two. There is one epsilon transition that allows you to skip the match, and one that adds a loop.

Greedy and Lazy Quantifiers

Let’s say you have a regex “a*” and the input is “aa”. By default, “a*” quantifier consumes both characters “a” and only then returns a match. This behavior is called greedy.

Some regex engines allow you to change this behavior and make quantifiers lazy by adding a question mark after the quantifier, e.g. “a*?”. In general, this is implemented by reversing the order of the transitions. By default, the first transition from a quantified expression performs a match. With a lazy quantifier, the first transition is the epsilon transition that skips the match. It also depends on the way matcher is implemented – this will be the focus of the next and final article.

Range Quantifier #

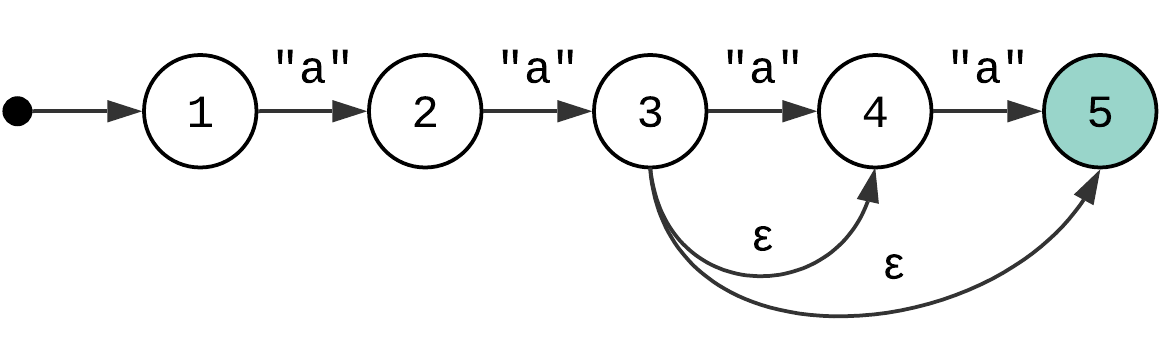

Range quantifiers might take multiple forms, but they can all be implemented using the same approach. Let’s take a pattern “a{2,4}” as an example. It matches the character “a” from 2 to 4 times. The trick is that it is essentially a syntax sugar for “aaa?a?. And it means that there are at least two ways to implement range quantifiers:

- On parser level, by preprocessing the pattern and expending every instance of range quantifier into a simple combination of characters and other quantifiers

- On compiler level, by repeatedly compiling the quantified expression to produce more than one instance of it, and applying quantifiers when necessary

If you’ve noticed, this state machine doesn’t actually represent “

aaa?a?”. It is closer to the form of “aa((a)?a)?”. And this is important, especially if the regex engine uses backtracking and you want to reduce the amount of it. We will talk more on the subject in the next article, stay tuned.

Alternation #

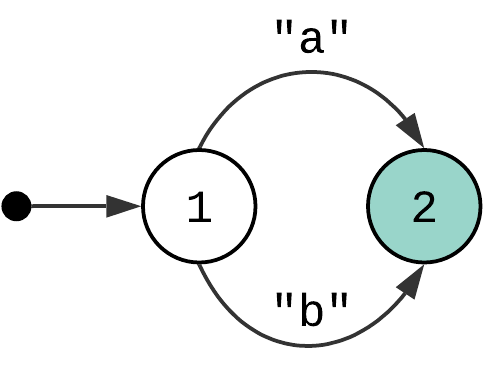

Alternation construct (the vertical bar “|”) matches the expression either on the left or the right side of it. For example, “a|b” pattern can be represented with the following state machine:

Just like with quantifiers, the left and the right side of the alternation is not limited to simple Match Character patterns, it can be any pattern. And just like quantifiers, it poses some challenges in terms of how to “run” the state machine with multiple choices, which we will focus on in the next article.

Anchors #

Anchors, like quantifiers, can be implemented using epsilon transitions (anchors don’t consume characters). But, unlike quantifiers, these transitions will have conditions depending on the type of the anchor. For example, end of string anchor (“$”) will create a condition which checks whether the input is empty (or whether the current character is a newline (“\n”) in a multiple mode).

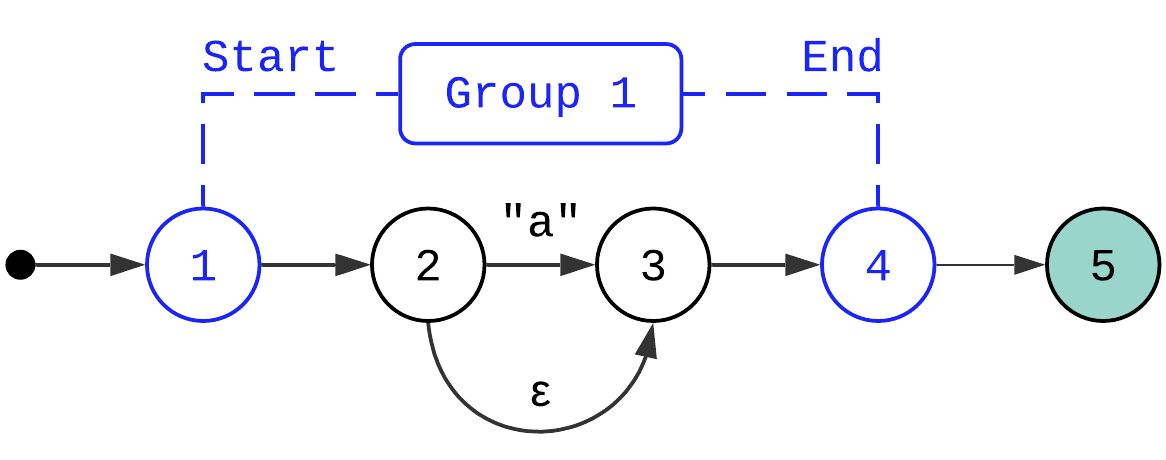

Groups #

A grouping construct is an odd one. The problem with groups is that they can’t be represented only using state machines. The problem is specifically with the “capturing” part – when a regex engine matches a group, it needs to capture the matched string and return it to the user. Another challenge is that a single expression can contain multiple capturing groups, including nested ones.

Here is how I ended up implementing groups in Regex:

The idea is that you “sandwich” a state machine delineated by the group between two “technical states” (in this case, states 1 and 4). The engine remembers which states are the start and the end states of the group. Every time the matcher enters the state which is an end state of the group, it captures the part of the input string beginning from the position on which the “start” state was previously encountered. If the group has a quantifier like zero or more quantifier applied to it, the matcher only captures the last match.

Debug Symbols #

So you compiled a pattern into potentially hundreds of states, each identical to the other. How to make it possible to debug it?

When you debug Swift or Objective-C code, Xcode is able to tell for each assembly instruction which part of the original code it represents. We should be able to do the same. In our case, there should be a mapping between each state of the state machine to the original pattern. With this information you should be able to log all the needed information when matching the input.

Here is as an example of the debug console logs produced by evaluating pattern "a|b" against the input string “a” (the formatting is still work in progress):

– [0, a]: >> Reachable ["State(0, Start, Alternation]"]

– [0, a]: Check reachability from State(0, Start, Alternation)

– [0, a]: State reachable, consuming 0, State(1, Start, Character("a"))

– [0, a]: State reachable, consuming 0, State(2, Start, Character("b"))

– [0, a]: Check reachability from State(2, Start, Character("b"))

– [0, a]: State NOT reachable, State(3, End, Alternation)

– [0, a]: Check reachability from State(1, Start, Character("a"))

– [0, a]: State reachable, consuming 1, State(3, End, Alternation)

– [0, a]: << Reachable [State(3, End, Alternation)]

– [1, ∅]: >> Reachable [State(3, End, Alternation)]

– [1, ∅]: Check reachability from State(3, End, Alternation)

– [1, ∅]: Found a potential match, State(3, End, Alternation)

– [1, ∅]: Found a match Match(fullMatch: "a", groups: [], endIndex: Swift.String.Index(_rawBits: 65537))

What’s Next #

As usual, you can find the full compiler implementation at kean/Regex. In this article, we’ve learned about finite state machines and how they can be used to represent some (or most) of the regex constructs. There is only one part left – matcher!

NFA vs DFA (Additional Reading)

Most of the state machines in the article were non-deterministic (or NFA). The moment you introduce epsilon transitions you add non-determinism. Non-determinism means that a state machine has multiple valid transitions from the same state and with the same input. Most of the regex engines use NFA but there are some that use DFA. I’m not covering the later in the series.

References

- Robert Sedgewick, Kevin Wayne (2011), Algorithms. 5.4 Regular Expressions, ISBN-13: 978-0321573513

- Ole Begemann (2017), Strings in Swift 4, excerpt from Advanced Swift book

- NSHipster (2018), CharacterSet

- Microsoft (2017), Details of Regular Expression Behavior