I love using Swift and have no thoughts about switching back to Objective-C, but that’s no longer a conversation because Swift is a de facto language on Apple platforms. During the first few years of Swift, I had complete confidence in its direction, and perhaps it was easier to make every change a slam dunk in the beginning. In recent years, there’ve been some questionable changes, the latest one being Data Race Safety in its current form in Xcode 16 beta.

Problem #

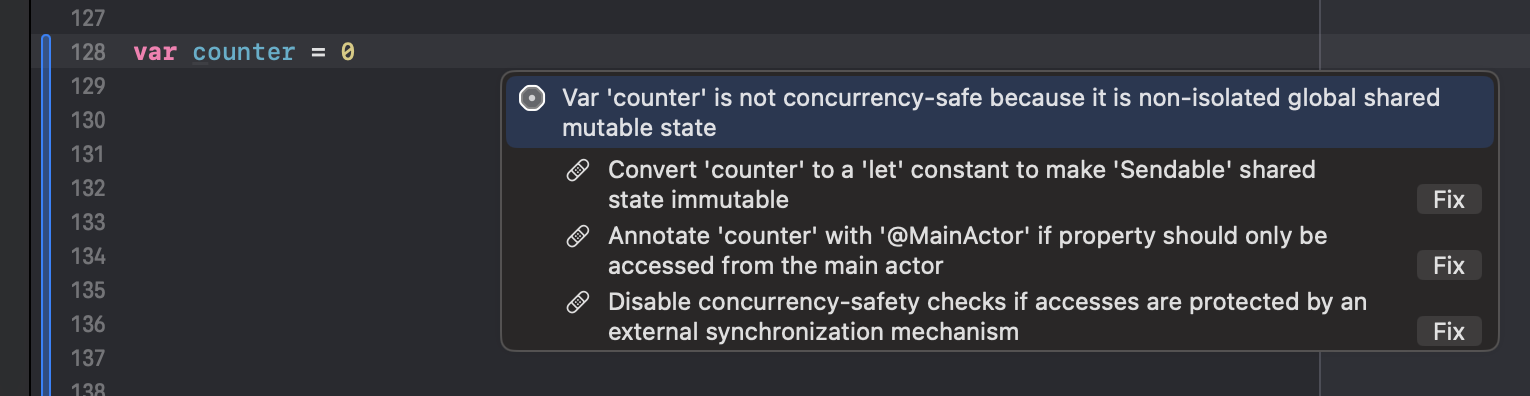

If you want to migrate a large codebase to support Swift 6 mode, you need to fix thousands of compiler warnings that become errors once you enable this mode. For example, if you have any global variables, they are now errors.

I think we might need to go back to the drawing board starting from right around here and re-establish what a compiler error is or should be:

- A syntax, linker or other error that prevents a compiler from generating the binary

- An obvious logic error where the code makes no sense under any circumstances

A compiler can have additional helpful diagnostics and show them as warnings if there is a high chance that the code is incorrect and/or unsafe. That has been my general framework for thinking about what a compiler is, and under that framework, a global variable by itself can’t be an error or a warning.

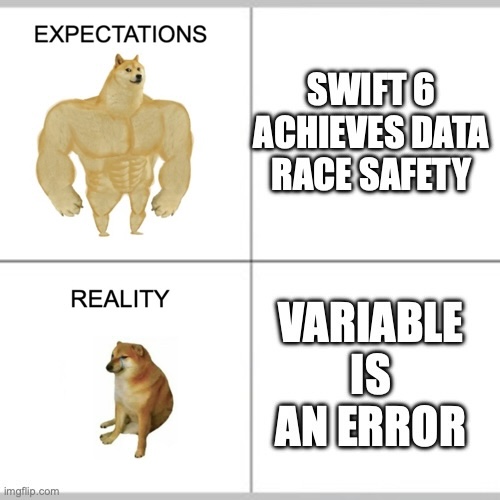

Data Race Safety is touted as one of the great Swift 6 features. You would expect the compiler to be smart enough to help you automatically find and eliminate the hard-to-debug concurrency issues and code smells, but the reality is quite different with too much of the work shifted to the developer.

OK, this is just for laughs. Maybe it’s the only reasonable way to implement it, but I think these design decisions combined with the lack of progressive disclosure is why this feature is often criticized and perceived the way it is. You want the compiler to help find the data races, and the data by itself can’t cause a data race – it’s how it’s being used down to individual properties, which is why Sendable also appears to be too blunt of an instrument.

There’s also been a notion that the new warnings are easy to fix. I’m sure some of them are, but that wasn’t the case in my experience. In my frameworks and apps, I had to carefully think about almost every individual instance and then often update tests, etc, which was extremely time-consuming even in smaller well-maintained codebases. Migration seems easier once you’ve done it, but at this point, it’s too late. I wouldn’t underplay how complex it is, especially anything related to closures and delegates.

It also depends on what kind of migration we are talking about. Unless you simply want to get your existing code to compile under Swift 6 by using @unchecked Sendable and unsafe(nonisolated) to essentially ignore most of the Data Race Safety system, you are looking at a rewrite of your concurrency code and the code that depends on it.

Suggested Solution #

The language, of course, should have first-class concurrency support, as outlined in the original Swift Concurrency Manifesto. Adding Async/Await and Actors has already been a huge win, but everyone is still in the process of adopting these new APIs. Eliminating data race issues at compile time is also a compelling idea, but I think neither the community nor the features are ready. Fortunately, there seems to be an easy fix to ensure that the migration goes smoothly and everyone is happy:

- Turn concurrency errors into warnings

- Make the warnings optional and unbundle them from the Swift 6 mode

- Continue iterating without locking the design down

In the ideal world, I would love to have more granular control over the types of warnings and errors the compiler produces, depending on what you can tolerate in your project. If data race safety is a compelling enough feature, people will enable it. There are also questions about whether it should be enabled by default and whether its current design can allow it to be enabled by default considering the lack of progressive disclosure.

Every project is different. Some apps, and I have an iOS app like that, run entirely on the main thread. For them, this change does nothing, but perhaps a better option would’ve been to implicitly treat every declaration as confined to the main actor. In some apps, the extent to which they use concurrency is limited only to making network calls – another scenario where opting out of the main actor seems like a better option. And there is code written for prototypes, debugging, testing, validation of ideas, or any other code where high standards don’t apply in which you don’t want any SwiftLint warnings, and likely no concurrency warnings and definitely no errors.

Aside #

This is pure speculation, but knowing how corporate politics work, I think one of the issues with Swift is that some group within Apple thinks of Swift as a product in itself and not as a means to an end like how Objective-C has always been treated. It leads to time constraints and impossible expectations being set for the teams.

With ten years in, there are some legitimate questions whether the recent changes have resulted in the productivity gains, which is ultimately the only thing that matters. Many new features have been syntax sugar, including property wrappers, result builders, multiple trailing closures, if expressions, and more. Swift now has levels of syntax sugar often surpassing scripting languages. I don’t necessarily say that it’s a bad thing, and as a counterexample, Async/Await, the new ownership model that follows the progressive disclosure principles, improvements to generics and incremental compilation, have all been welcome.

Speaking about compile time, one of Swift’s original premises was that it was “fast,” and you would expect it to apply to the compile time. However, with the current slow compilation, developers have to go to extreme lengths to work this around, including reinventing header files by creating protocol-only modules, which Swift was designed to eliminate. If there was a way to disable some of the language features to improve compile time, I would do it in an instant. I’m bringing this up because I wonder what the impact of data race safety is going to be, especially once it gets upgraded with more advanced techniques for eliminating false positives.

Final Thoughts #

I hope Apple returns to Swift’s original tenets and makes it fast and simple, focusing on productivity gains over everything else, and reduce the amount of work the developers need to do, not increase it.