As engineers, we are always looking for ways to reduce costs and still satisfy all of the project requirements. We have to be very careful to only invest the engineering time into things that truly matter. This is just basic economics. And that’s where the debate about unit testing comes in. Is it worth it?

Proponents of unit testing claim that tests help you understand the requirements, give you confidence during refactoring, serve as executable documentation, reduce defects, facilitate good design, and reduce global warming. So what’s there not to love?

Unfortunately, it’s incredibly easy to write poorly designed tests that don’t test anything important, which are slow to run, which are hard to maintain, and which make refactoring harder, not easier. It is possible to have negative value tests. Writing tests is easy. How to write good ones?

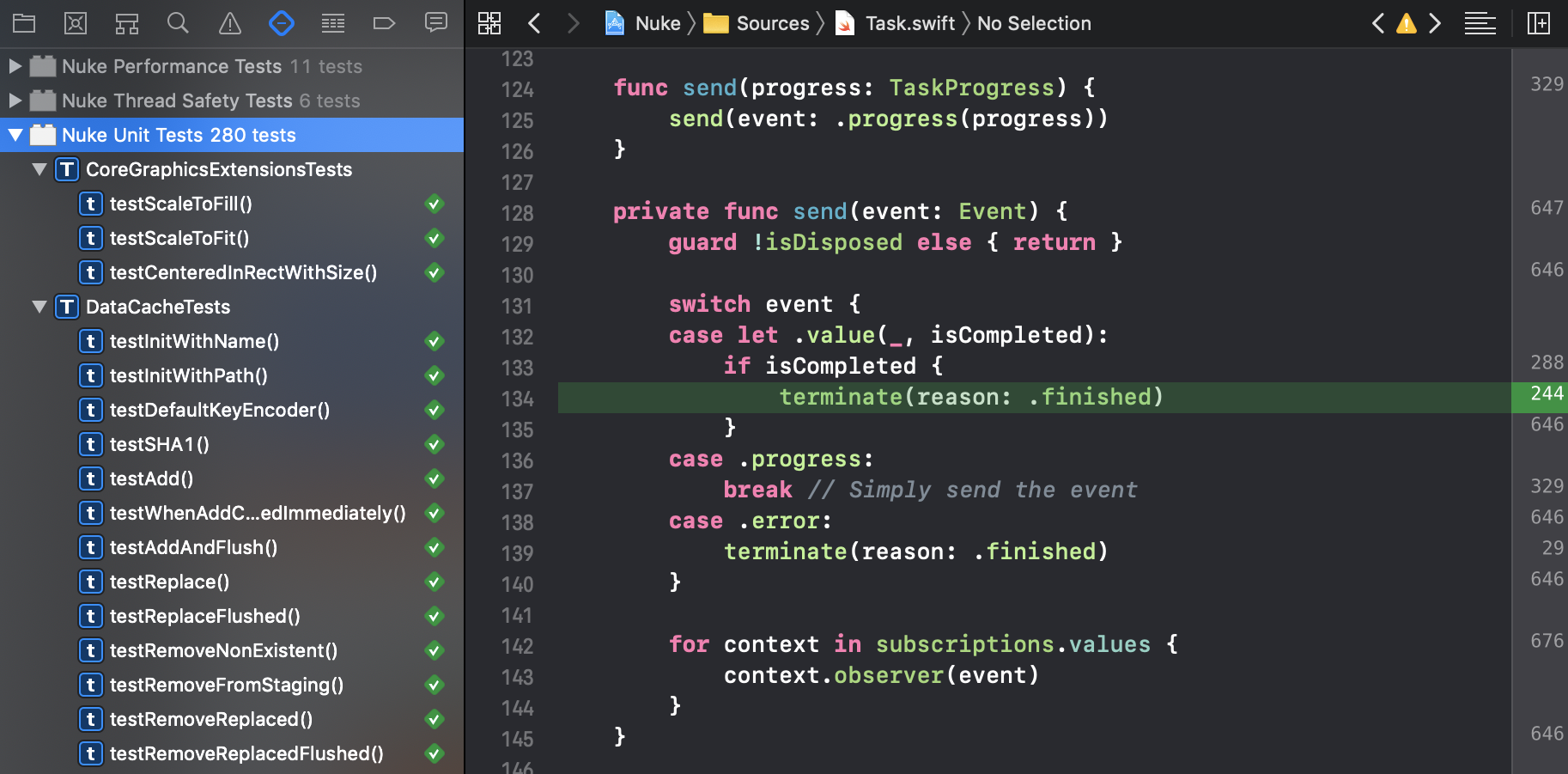

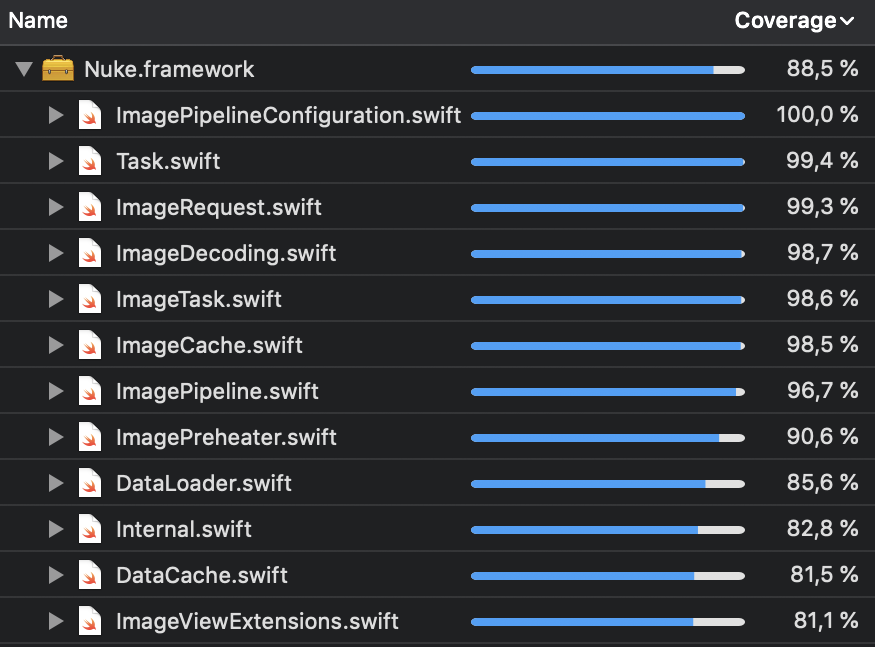

Code Coverage #

First, we need to set the right goals. For example, achieving 100% code coverage. An optimistic goal. Easily measurable. That’s what we are going to optimize for, right? No.

Code coverage is an instrument. It shows what areas of the app are not tested yet, nothing more. Improving coverage is not a goal in itself. It’s a feel-good metric to pump up, but it’s an unreliable indicator of how good your test suite is. Code coverage says nothing about the quality of the tests. Improving coverage is worthless if it doesn’t attribute to an increase in the quality of the deliverables. Measure quality1, don’t focus too much on code coverage.

Code coverage also ignores priorities. Not every piece of code is the same. You get the most value by covering the code that is mission-critical, complex and is a common source of regressions. Good testing is based on careful analysis and risk management. You have to have skills in this area, or you are likely to waste a lot of time and effort which could be spend elsewhere.

XCTest vs Quick #

There are two primary options on iOS: XCTest and Quick. I used both extensively, and my opinion is stick with XCTest. XCTest is easier to learn and use, and it has great Xcode integration.

Quick has some good ideas in it, but I think learning and integrating it is a waste. It also doesn’t play well with Xcode. For example, you can’t jump to a test by clicking on it in Test Navigator. So when a test fails, you can’t open it quickly, which is kind of a terrible experience. There is also no way to run a single test – you have to change it() to fit() in code. There are a lot of issues like that.

Nothing prevents you from writing readable tests which focus on behavior with XCTest. Make sure to extract duplicated code, and keep tests well-structured:

func testCreateResumableDataWithMissingValidator() {

// Given response with missing validator

let response = HTTPURLResponse(headerFields: ["Accept-Ranges": "bytes"])!

// When

let data = ResumableData(response: response, data: makeData())

// Then

XCTAssertNil(data)

}

Unlike Quick, you don’t have to spell out everything that you do, avoiding duplication. Quick has a sense of novelty, but chances are, you ain’t going to need it. A valid reason to use Quick2 is if you truly practice Behavior-Driven Development, BDD. I haven’t seen this done anywhere, so I can’t comment on it.

Testing Pyramid #

You most likely heard about Testing Pyramid. The idea is that unit tests are cheap and UI and integration tests are not, and that you need to have more of the former. I partially agree with this, but I would like to point a couple of things.

1. UI and integration tests are expensive for a reason. It’s known that the root cause of 99%3 of the defects in iOS apps is UIKit. And you can’t test it with just unit tests. Yes, unit tests are cheap, but they are no substitute for UI tests. Make sure you have both!

2. When added retroactively, unit tests can be more expensive to write than UI tests. And more risky – rewriting systems to make them testable is hard. Before sinking your teeth into refactoring, consider adding UI tests.

3. The reality of many systems and apps is that not all of their components have perfectly designed APIs. Getting back to risk management, I think you are much more likely to introduce a defect by not anticipating how the component you are changing is used somewhere else in the system. This is why I think that for complex systems integration tests are far more important than unit tests.

I think that the testing pyramid is no longer relevant. Hardware is cheap. UI automation tools are better than ever. And, on the other hand, modern programming languages have type-safety features that make a lot of unit testing obsolete. The communities that seem to be the most vocal about TDD and unit testing are Ruby and JavaScript. In these dynamic languages even changing the name of a function can be dangerous. But Swift is very different, it is safe. If you design your components well, they already read like a specification4 and there is very little value to test them in isolation.

What You Should Test #

When should you use unit tests? MVC can help you answer this question. Most people agree that you should cover Model layer5 with unit tests, and you shouldn’t cover View layer. But there is also this grey area, Controller.

MVVM and MVP allow you to test ViewModels or Presenters (Controller layer) in isolation. Some might say that this is the whole point of these architectures, otherwise you are better off sticking with Apple MVC. However, there is a problem with these types of unit tests.

Testing ViewModels or Presenters typically requires a significant amount of effort, primarily because of all the mocks that you need to write or generate. And when you mock, you’re removing all the confidence in the integration between what you’re testing and what’s being mocked. In my experience, these kinds of tests don’t reduce the defects6 and they often end up being more complicated than the actual code.

The more your tests resemble the way your software is used, the more confidence they can give you.

Am I saying that you should not test ViewModels and Views? Absolutely not. What I mean is that you should probably not test ViewModels in isolation by mocking all of the dependencies. This is where UI and integration tests come in. ViewModels can be a fantastic “end” in integration tests.

There is also an unintendend consequence of creating too many unit tests for ViewModels with too many mocks – they become a barrier to refactoring7. You make a change in a commonly used service and instead of only updating unit tests for this service, you also have to update all of the ViewModels and all of the mocks that they use. Eventually, these tests erode without significant investment in their maintenance.

High Quality Tests #

I’m not going to focus too much on the nitty gritty details of how to actually write the unit tests. It all comes with the experience. But I would still like to share a couple of tips:

- Treat test code as well as you treat your app’s code. Apply all of the good engineering principles that you know. Avoid duplication, refactor, strive for readability. Have a plan for how you are going to maintain your tests.

- Follow the FIRST principles, they are universally applicable

- Before even writing tests, you must first think about the surface area of your APIs. You can’t write good tests on top of a poorly designed API. And, on the other hand, a well-designed API makes it much easier to write good unit tests. This is a reinforcing cycle.

If you want to learn more about unit and UI testing with XCTest, I would recommend going through the WWDC videos, including:

I would also recommend going through Software Testing Guide by Martin Fowler.

Final Thoughts #

Write tests. Reward value, not volume. Optimize for confidence. Don’t create too many tests, there is such thing as too much of a good thing.

Think carefully about where to invest your efforts. Don’t focus on just one kind of testing. Unit tests, integration tests, UI tests, snapshot tests – they all have their cost and they are all useful in unique ways.

Prioritize. Cover the mission-critical scenarios first. And maybe you don’t need to cover this tiny view model which never changes and never breaks.

Experiment. Even if you are doing some of your testing wrong, the risks are low – you are not shipping this code in production.

Take the advice from this article with a grain of salt. The culture of test automation on iOS and some other Apple platforms is relatively young. I can’t wait to see where it goes next.

References

- WWDC 2019, Testing with Xcode

- WWDC 2018, Engineering for Testability

- WWDC 2016, UI Testing in Xcode

- Martin Fowler (2019), Software Testing Guide

-

Measuring quality is a topic in its own right. Your team should have visibility, e.g. via weekly report, in how many defects there are total and per story, how quickly the defects are closed, how many regressions there are per each version. If that’s what everyone sees, that’s what the team is going optimize. ↩

-

Nimble is a separate framework and can be used with XCTest. So if that’s your cup of tea, you have options. ↩

-

I made this number up. UIKit is a problem because its answer to every little programmatic error is crash. Fortunately, Apple is making a u-turn with SwiftUI. ↩

-

I’m also skeptical about one of the commonly listed advantages of unit testing – serving as executable documentation. You know what else serves as great documentation? Documentation. The problem is, unit tests are not as easy to read as you might want. If the behavior is not documented, I will just go and read the source code every time. ↩

-

This includes business logic, algoritnms, parsing, storage, migrations, etc. But don’t test configuration. And keep your models fat! ↩

-

I wish I could back up this claim with some hard numbers, but all I can say is that this is based on my extensive experience with both MVP and MVVM. ↩

-

Did I just say that unit tests become a barrier for refactoring? Yes, especially for relatively simple components covered with too many too basic unit tests. Nobody wants to maintain or update the tests which they perceive to be too basic and of low value. ↩