Two months ago, I started an experiment of building a non-trivial production-ready app targeting all Apple platforms using only SwiftUI. It was an incredibly fun and challenging experience, but part of the journey is the end. The goal of this post is to provide a glimpse of how it was done.

I’ve been working on iOS for many years now. When Apple shipped SwiftUI, I saw it as a perfect opportunity to explore other Apple platforms.

The best way to learn something is to build a project. SwiftUI has two main advantages: iteration speed and code reuse across Apple platforms. I had just the right idea for a project that could take advantage of both.

Project #

There is always this friction when it comes to debugging native apps: you can’t inspect anything that happens behind the scenes unless you use special tools, not even network requests. That’s not the case on the web with tools like Safari Web Inspector. I wanted to bring something similar to native apps1. This is how Pulse was started.

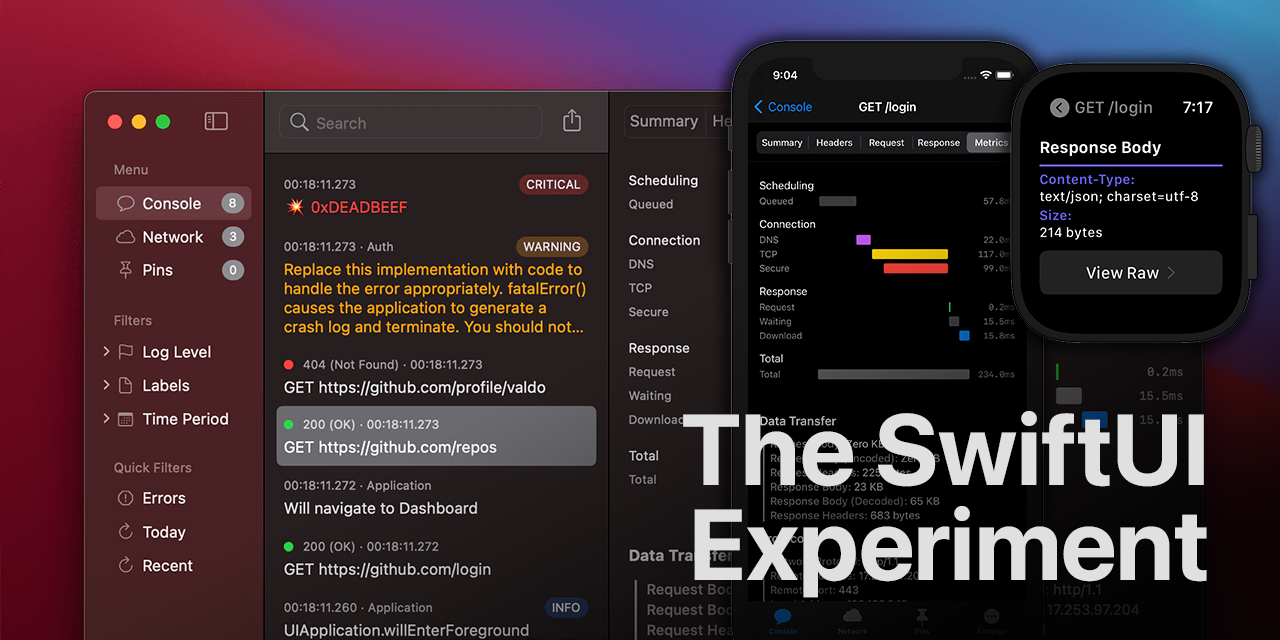

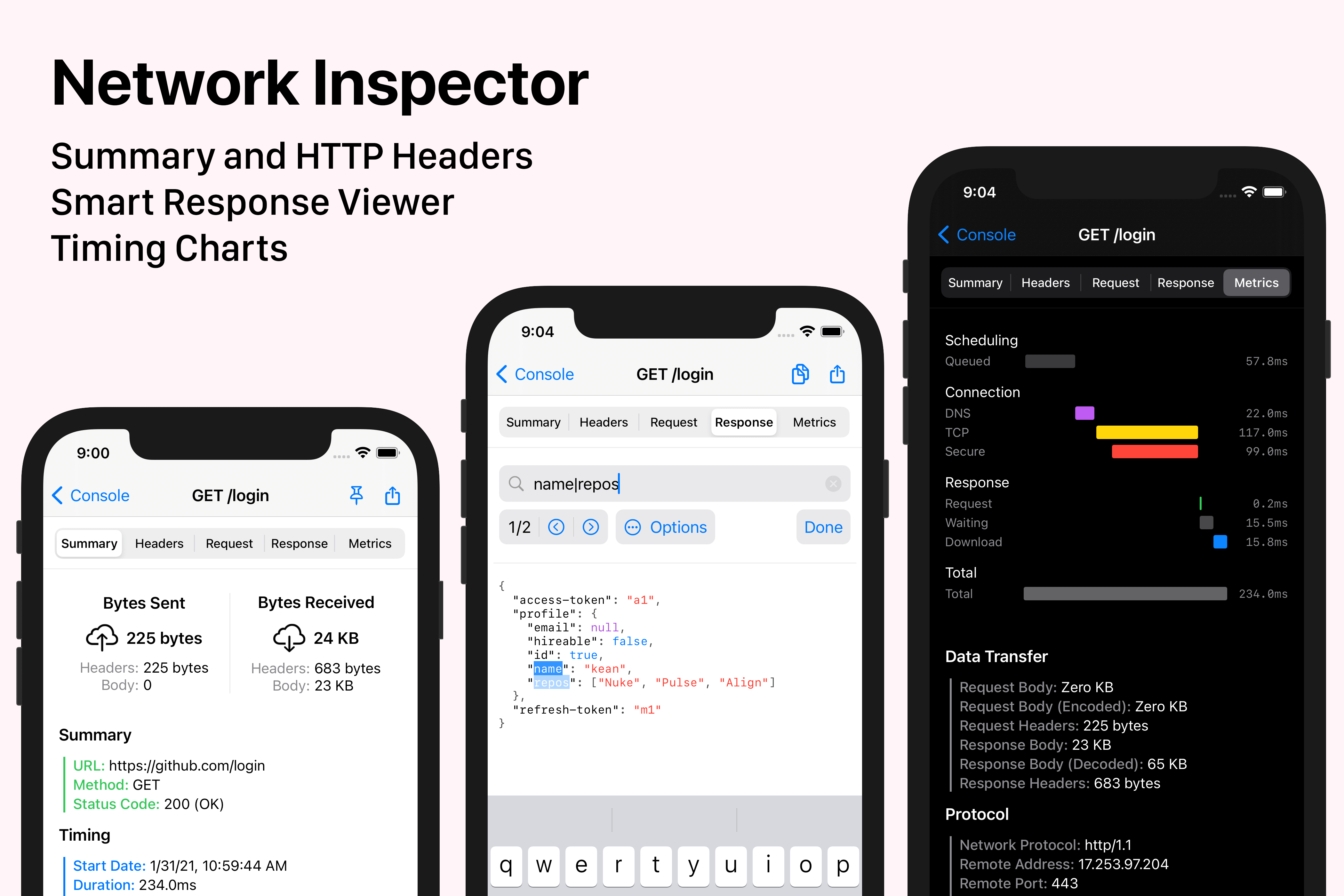

What is Pulse? It’s a persistent logger with a network inspector, but not just a tool. It’s also a framework.

- PulseCore.framework (iOS, macOS, watchOS, tvOS) provides a logger itself and a network proxy for automatically capturing network requests

- PulseUI.framework (iOS, macOS, watchOS, tvOS) containing all the UI components you’ll see on the screenshots

- Document-based Pulse apps (iOS, macOS) to view logs shared from other devices

Pulse is distributed as binary frameworks. More in “XCFrameworks”.

As a developer, you integrate the frameworks into your app and configure them to capture logs2 and network traffic. You then add a way to display a Pulse console to view logs right on the device (can be a shake gesture, for example).

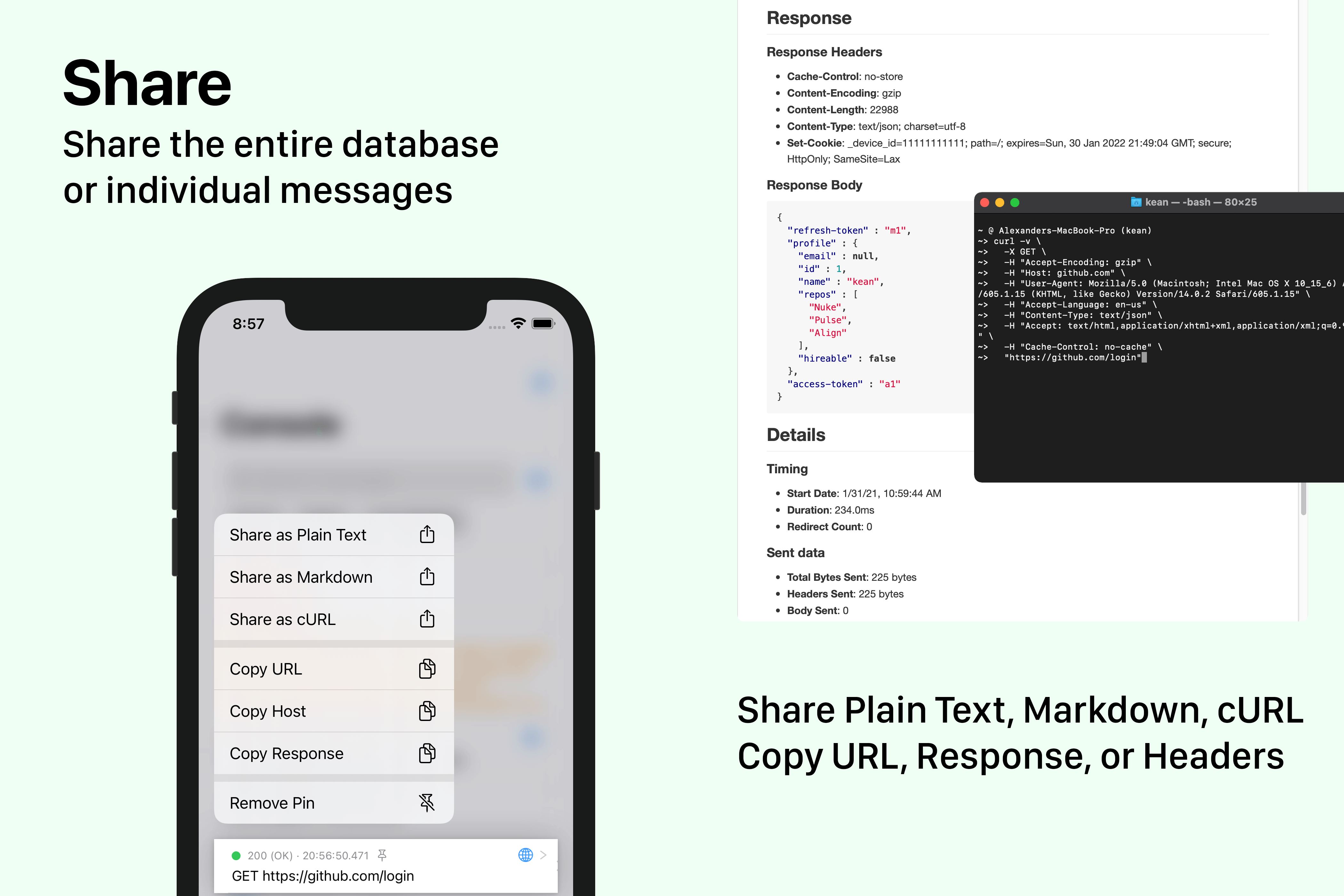

As a QA engineer testing the app, you can view the network requests right on your iOS device without installing any special tools. And when you find a defect, you can send the logs to the developer using any native sharing mechanism. The developer can view the shared files using a dedicated Pulse app available both on macOS and iOS.

Adding a custom document format was a story on its own which I covered in “What’s a Document”.

Pulse Open Beta #

I’m thrilled to announce that Pulse Open Beta starts today. You can find the download links in a dedicated repo. If you wanted to try to make it crash, now is your chance.

I want to thank all early sponsors. You are the reason I was able to reach this stage! It was an exhilarating journey with so much feedback, including from SwiftUI engineers at Apple. I’m humbled and grateful.

Development #

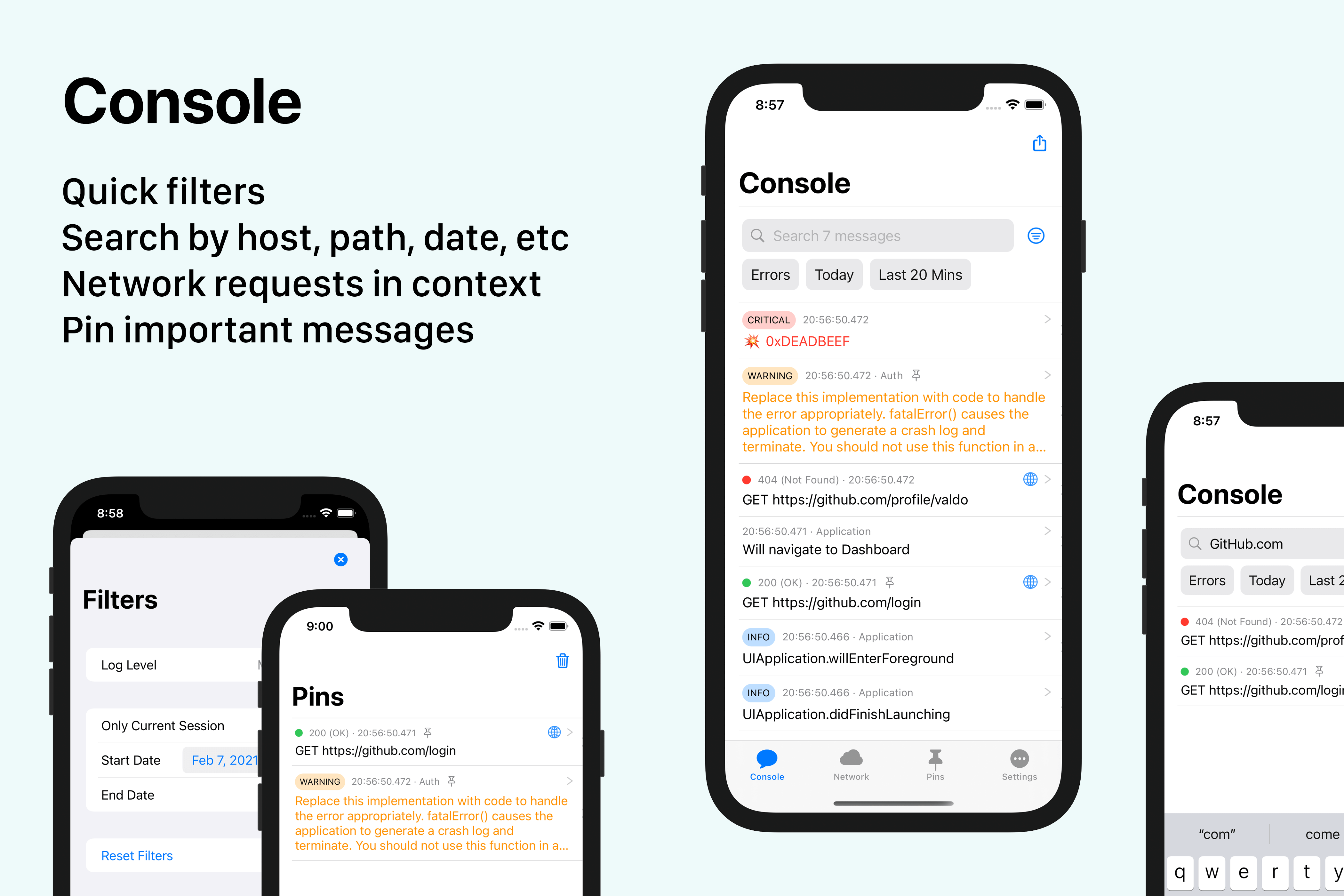

iOS #

I started with the platform I felt the most comfortable with – iOS – with the initial goal to truly learn SwiftUI by putting it through its paces. After all, before building the app, I had to design it. I wanted to avoid the distraction of having to learn a new UX paradigm.

I built the entire app using SwiftUI with a couple of minor exceptions: UITextView, UISearchBar, and UIActivityViewController. But it was a simple matter of wrapping them using UIViewRepresentable. The rest of the systems: layout, data flow, and the existing SwiftUI components, worked perfectly.

For iOS, I challenged myself to use only SwiftUI APIs available on iOS 13. But what do you do if your app supports earlier iOS versions? PulseUI.framework compiles on iOS 11, but most of the components are marked with @available attributes.

@available(iOS 13.0, *)

public struct ConsoleView: View {

// ...

}

You can integrate Pulse in practically any app, but make it available for the development team only on devices running iOS 13 and later.

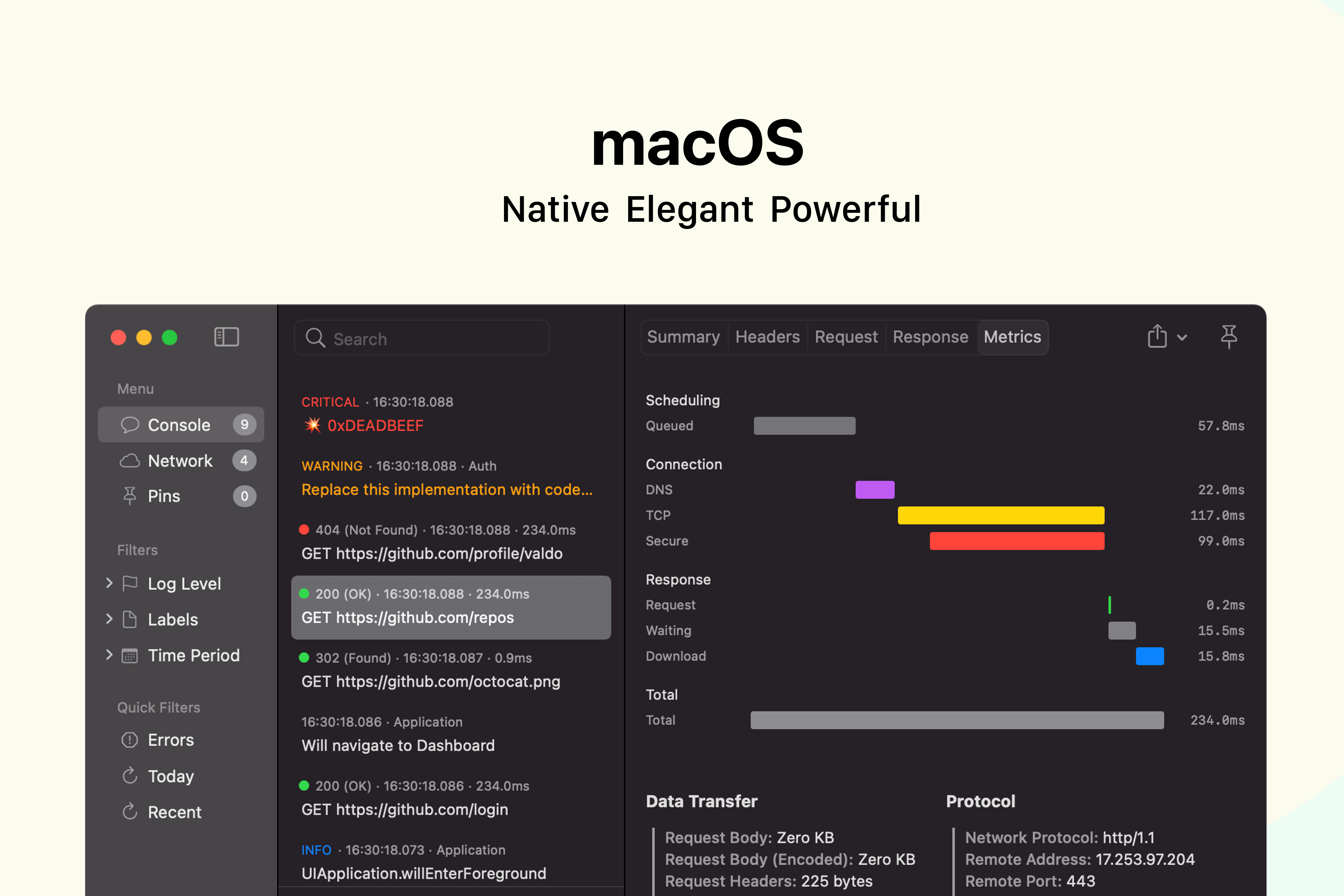

macOS #

The next milestone was macOS. When the time came to work on it, I was anxious. I had no idea what to expect from SwiftUI on a Mac. But thanks to the new SwiftUI APIs and the Big Sur design changes, everything just made sense!

I was so excited after building the macOS version that I wrote an optimistic take on how AppKit was done, only to correct myself later after I had spent more time on optimization. I encountered massive issues with List performance and replaced it with an AppKit version, including AppKit-based cells and context menus. Fortunately, I was able to get it to work with the SwiftUI navigation system. And it was worth it. The optimized version is fast even when working with hundreds of thousands of messages.

I wrote the rest of the macOS apps using SwiftUI, even the more challenging aspects of macOS: commands Commands, window management (WindowGroup, handlesExternalEvents, focus management, etc.

At the core of the macOS is a triple-column navigation setup. It was hard to find accurate information about it in SwiftUI, so I covered it in “Triple Trouble”.

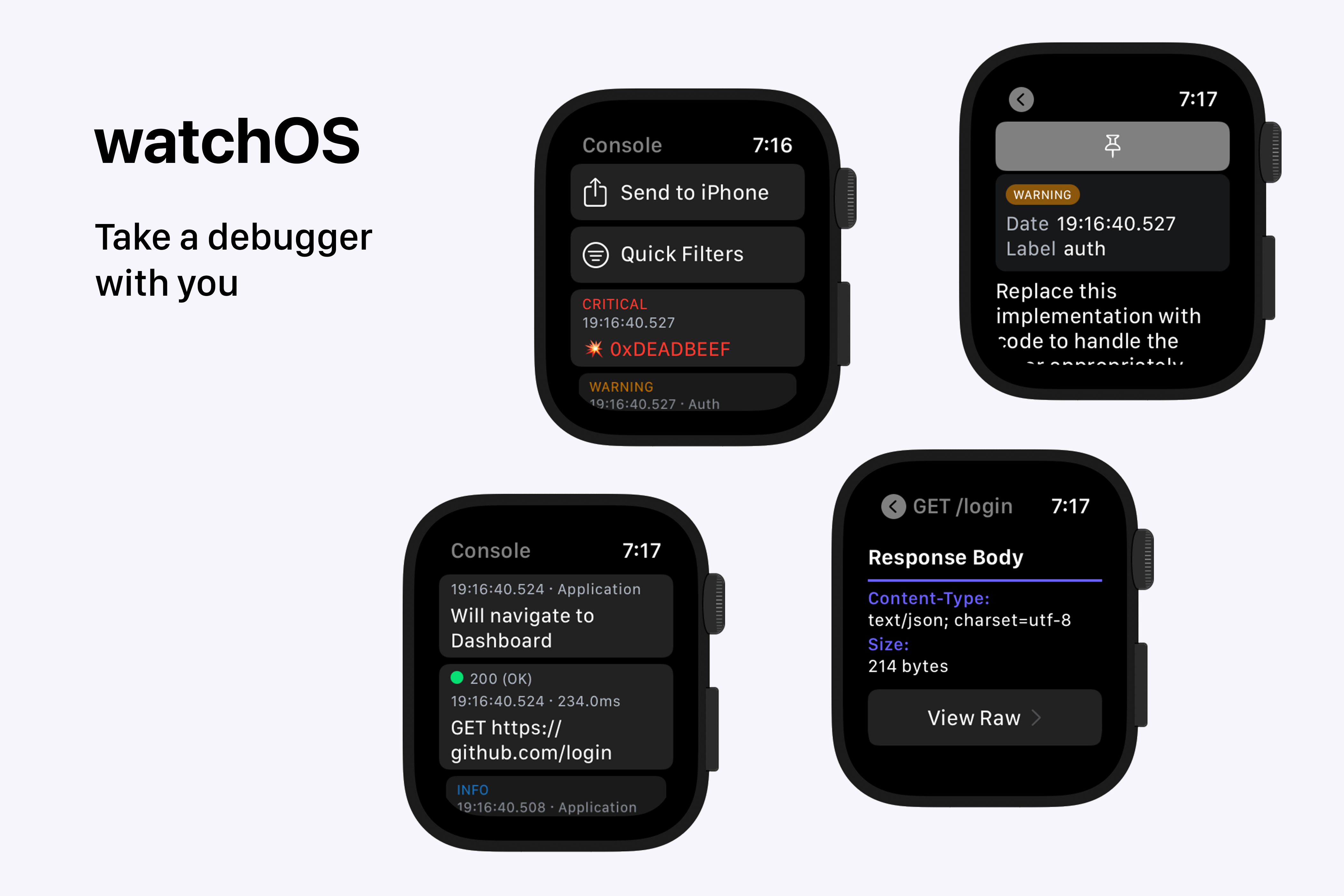

watchOS #

When I started working on Pulse, I challenged myself to push SwiftUI to the limit and not rely on the platform-specific code. I had my eyes on the prize that in time I’ll add support for all Apple platforms, including watchOS and tvOS. It was time to reap the benefits.

After designing and implementing a macOS app, watchOS was a walk in the park. SwiftUI feels the most at home on this platform. It isn’t surprising since it’s the only way to develop a watchOS app. When you use SwiftUI, you know that it gives you the full power of the platform.

Why bring Pulse to watchOS in the first place? Many of the watchOS apps are designed to be used outdoors, during physical activities. You won’t be carrying a computer with you to a gym, will you? Pulse is a perfect tool for this.

With Pulse, you can view network requests and logs right on your wrist. Logs are recorded persistently, and you can share them at any time, for example, to iOS. Pulse for iOS offers a great experience and a feature-set on par with a macOS version.

The most challenging aspect wasn’t the implementation, but figuring out what features to build (and, more importantly, what not to). I was so excited deploying an app to it for the first time. It brought up the memories of doing the same on iOS many years ago!

You can learn more about Pulse for watchOS in “Time to Log”.

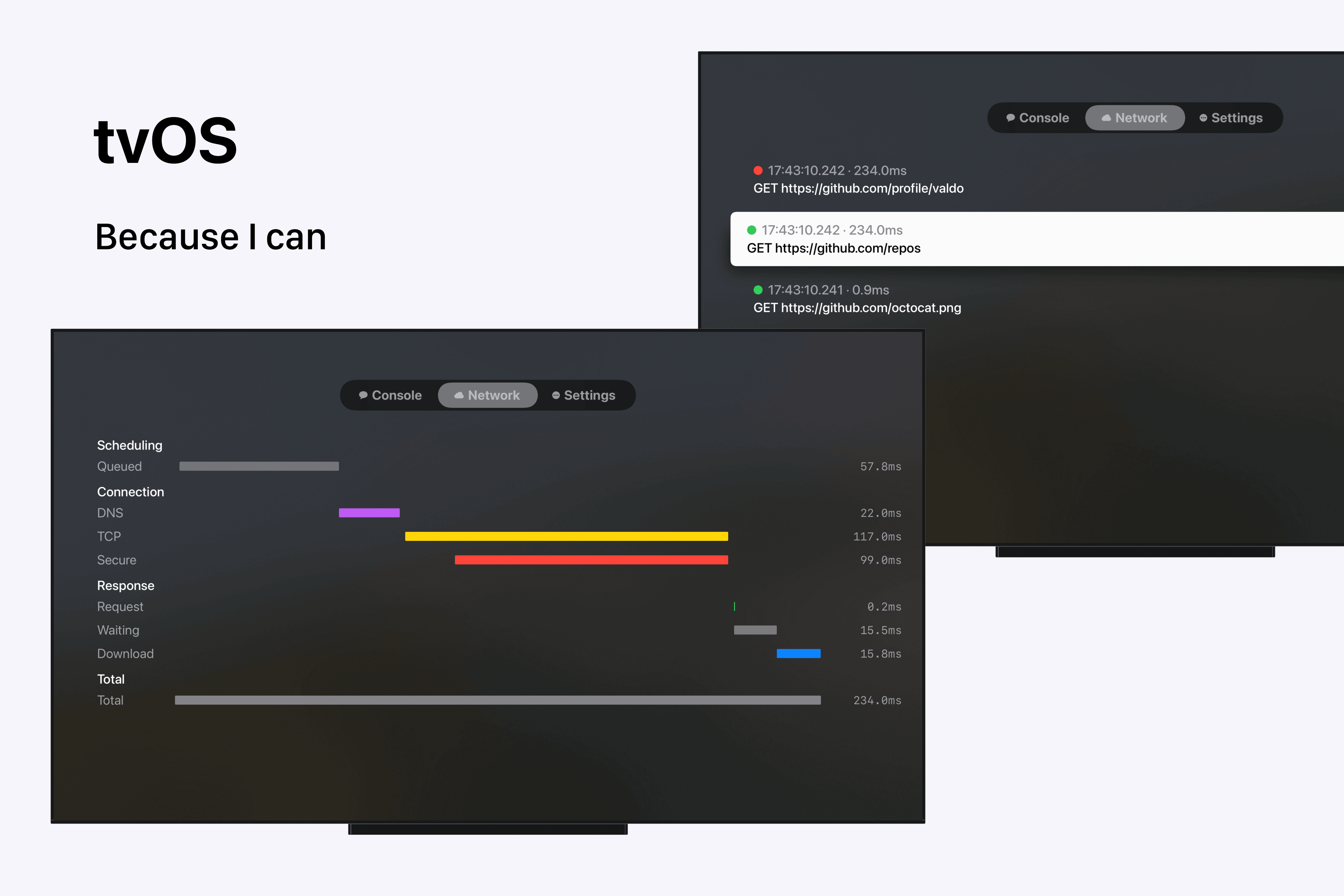

tvOS #

I’m not entirely sure who needs Pulse on tvOS, so I haven’t prioritized it. But since I already covered the rest of the platforms and had the energy to continue, I decided to give it a go. Mostly for fun, and it was!

I was surprised to learn just how powerful the API for this platform is. It runs UIKit. There is a bit of a mismatch between the APIs power and the typical app design constrained in a similar way the watchOS apps are: limited user input, can’t cram too much on screen. I ended up reusing a lot of the elements from watchOS.

It took me four hours to build a watchOS version and about three for tvOS. I knew nothing about these platforms when I started. I wasn’t always able to reuse the code, but I reused the knowledge – SwiftUI APIs are essentially the same on all Apple platforms.

Retrospective #

There has rarely been a framework as scrutinized as SwiftUI. Is SwiftUI ready for production? Contrary to the common misunderstanding, there is no binary answer to that question. It is in production. Is it good?

Instead of theorizing about it, ad nauseam and ad infinitum, I went ahead and built a project with it – the ultimate test. For Pulse, SwiftUI was undoubtedly the right tool. But there are also some aspects of SwiftUI that I’m not crazy about.

Good #

Iteration Speed

Saying that developing with SwiftUI is fast is an understatement. It feels orders of magnitude faster than UIKit/AppKit3. Canvas, layout system, data flow – all designed for maximum productivity.

Code Reuse

Pulse consists of ~10000 lines of code. PulseCore is 3000 lines (store and network proxy). The rest (7000 lines) takes PulseUI. About 85% of the UI code is shared between platforms. That’s a lot. It’s astonishing how much UI you can fit in 7000 lines. SwiftUI, it gets the job done!

Layout System (Good Parts)

SwiftUI no longer uses Auto Layout, gone all of the cruft introduced over the years. SwiftUI has a new layout system designed from the ground up to make it easy to write adaptive cross-platform apps.

People love to praise Flexbox. I use it on this website too, and I’m not crazy about it. I very much prefer SwiftUI stacks, grids, and spacers.

Annoying Auto Layout warnings are also gone (but at a cost). I wrote about the SwiftUI layout system before, but my opinion has changed, thus the “Good Parts.”

Data Flow

SwiftUI uses a reactive framework, Combine, for updating views. But as a user, you don’t even think about it when writing SwiftUI code. You get all the advantages of reactive programming (simple and consistent data propagation) and none of the drawbacks.

- You express business logic naturally using plain Swift properties and methods

- It’s much easier to debug views and view models. You can set breakpoints and query any of your view model state.

- It’s beginner-friendly. No need to learn

combineLatest,withLatestFrom, and other complex stateful operators. You don’t needflatMapto send a network request. - It is more efficient because you avoid creating massive observable chains

Data flow is probably my favorite aspect of SwiftUI. I was so impressed with it that I went ahead and built a prototype of a similar system for RxSwift using reflection and associated objects. Why haven’t we thought of this before?

Bad #

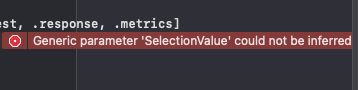

Generics

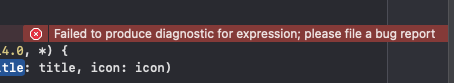

It’s hard to tell just how much time I wasted fighting the SwiftUI generics. I acknowledge that I don’t fully understand the performance benefits of types in SwiftUI, but I can’t help but wonder if it was worth it. The abundance of generics leads to poor code completion, error messages, documentation, and ergonomics. These are legitimate issues.

My most common mistake is using & instead of $ and then wasting 20 minutes figuring out why there is an unrelated type-system error 5 lines from where I used &.

Layout System (Bad Parts)

Some basic things that are unproblematically done with Auto Layout are hard in SwiftUI, for example, matching the size of two views or aligning them. SwiftUI layout system is simply less expressive. The good things about it (stacks, grids, spacers) are easy to add to Auto Layout. And I still can’t build a complete mental model around the SwiftUI layout system. Auto Layout, on the other hand, makes total sense – it’s just math.

List

The SwiftUI components library is small, but the components it offers are well-designed and work great. Except for List. I simply wasn’t able to use it on macOS: junky scrolling, jumping scroll bar, slow reloads, delays when opening details, slow selection. I wrote a separate post on how to fix it. I’m still using List on the rest of the platforms where I only display a subset of messages by default, so the performance is acceptable.

Ugly #

Telescoping APIs

UIKit and AppKit pack a lot of power. The delegate-based approach is well-positioned to scale to any level of complexity. I’m curious to see how SwiftUI will tackle it. The dose of fluency it gives comes at the cost of not addressing the complex problems. I hope ScrollViewReader and 18 different List initializers will not become the norm.

Pitfalls

We exchanged the gotchas from UIKit with new ones in SwiftUI. Some examples:

- Forgetting a single period can cause a SwiftUI view to crash in a less-than-obvious way (screenshot in case the message gets deleted).

- SwiftUI frequently re-instantiates views and creates some of the view hierarchy in advance. It can lead to performance issues if you are not careful.

- You can access

StateandStateObjectvalues only frombody. - Putting modifiers in the wrong order. The most common example is using

backgroundbeforepaddingwith an unexpected result (unexpected compared to how most other UI frameworks work).

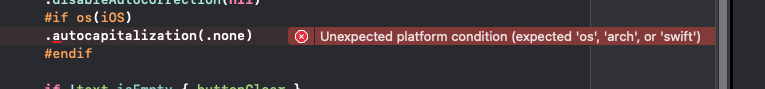

Conditional Compilation Blocks

It’s harder to add platform-specific code (or any conditional code really) in SwiftUI than in UIKit or AppKit. I’m not even starting on ViewBuilders. I won’t bet against DSLs or functional programming, but it forces you to find solutions for problems you didn’t have.

Updates

View Lifetime

I’m used to memory management in UIKit. You create a ViewModel and a View, View holds a strong reference to a ViewModel - nice and easy. SwiftUI makes this basic setup unnecessarily awkward.

ObservedObject makes no guarantees about the object lifetime4. Managing ViewModel graph manually is a pain. StateObject uses autoclosure making initializer injection a bit awkward to use (it’s possible using an initializer directly). Using DI with StateObject doesn’t make much sense in the first place because it gives you the wrong impression that you can change parameters without changing the identity of the view.

I figured data flow out with all its property wrappers, but I feel like this every time I explain them.

API Quirks

.disableAutocorrection(true) // disable autocorrection

.disableAutocorrection(false) // don't disable autocorrection?

.disableAutocorrection(nil) // ???

.disableAutocorrection() // ???

I tried to make sense of it, but I still don’t fully understand the logic. I never use the nil part. Regardless of the use-case, the naming is objectively poor.

Conclusion #

Back when the first iOS SDK hadn’t even launched, Scott Forstall told some developers to jailbreak iPhones to get a head start on development. And they did. SwiftUI is in its early stages, but there is already so much written on it. The developer community inspected every aspect of SwiftUI and came up with great workarounds for its current limitations.

This experiment proved, to me at least, that you can build production-ready apps using SwiftUI. Pulse performs well. It reuses a lot of code but is optimized for each platform. It has a ton of powerful features: deep-links, document-based apps, databases, powerful search, and filters. But if you decide to use SwiftUI, proceed with caution. It’s the second mouse that gets the cheese. You’ll still be the first mouse.

I hope you liked this series. It was meant to inspire folks to try their hand at SwiftUI and explore different Apple platforms. Some caution is still warranted. I always draw the line between the business needs and my personal passion projects. And again, the Pulse Open Beta is out. I hope you’ll like it! And if you want to read more from this series, boy, I have posts for you.

-

Time to Log

Designing and implementing Pulse for watchOS

-

What's a Document

A quick write-up on selecting a document format for Pulse

-

...But Not NSTableView

Integrating NSTableView with SwiftUI

-

AppKit is Done

Learn how to build delightful macOS apps using only SwiftUI

-

RxUI

Applying SwiftUI ideas to improve the developer experience of using RxSwift

-

Apple Documentation

Everything that is wrong with Apple's documentation

-

Triple Trouble

Implementing triple-column navigation in SwiftUI using NavigationView

-

XCFrameworks

Caveats of using XCFrameworks with Swift Package Manager

-

SwiftUI Data Flow

Everything you need to know about data flow in SwiftUI

-

SwiftUI Layout System

Taking a deep dive into SwiftUI layout system

This wraps up the series on Pulse. I’m completely exhausted. It’s time to unwind and get ready to start on a new project…

-

I learned after the fact that there were some similar open-source tools already available, like Netfox. But I was building my own thing with a primary focus on high-quality design and multiplatform support and didn’t use any of their ideas or code. The only dependency I used was ZIPFoundation that I already thanked in my post about document types and I’m currently sponsoring on GitHub. I can’t recommend it enough. ↩

-

If you are using SwiftLog, you can also install

Pulse.frameworkthat addsPersistentLogHandlerclass that can be used as SwiftLog backend. ↩ -

To clarify, it’s mostly Xcode Canvas that accelerates the development. You can use it with UIKit and AppKit just as well as with SwiftUI. If you already have a simple declarative wrapper on top of UIKit or AppKit, do you really need SwiftUI? ↩

-

“ObservedObject does not get ownership of the instance you’re providing to it, and it’s your responsibility to manage its life cycle.” – from WWDC2020: Data Essentials in SwiftUI. What it means is that if you create an ObservedObject in-place in the view, it will get re-created every time the view struct is re-instantiated, losing all of its state. So you need to inject it. ↩